Civil War taught how to influence news media. It nearly cost Lincoln re-election

The idea of using news media to spin a narrative and push a political agenda is hardly new. The Confederate Secret Service used that strategy to try and defeat President Lincoln.

The political neutrality of news media has recently been called into question, but as far back as the Civil War, opponents have understood the importance of controlling the narrative in the press — and have gone to great lengths to influence it to help sway elections.

Facing the overwhelming odds of the massive Northern armies, Southerners innovated and developed shadow warfare and covert operations to help even the odds, including attempting to manipulate news coverage of the war and erode Northern morale.

Deliberately opaque, the Confederate Secret Service was a real but unofficial hidden hand that lay behind these clandestine efforts to alter the course of the war. Various branches of the Secret Service attempted a number of techniques, including kidnapping officials, violence and trying to incite insurrection, but some believed using influence and money offered the best chance of success in stopping the war.

CIVIL WAR GENERAL SHERMAN'S SWORD AMONG RELICS HEADED TO OHIO AUCTION NEXT WEEK

While there was no official head of the Secret Service, Confederate President Jefferson Davis acted as its director, authorizing operations and working closely with a handful of officials. One arm of the Confederate Secret Service was overseen by his State Department, headed by Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin, sometimes called the "Brains of the Confederacy." Benjamin’s State Department trafficked in election interference, bribing members of the Northern press to craft a favorable Southern narrative.

One of their most important objectives was to try to influence the 1864 presidential election. Confederate Secret Service operative George Nicholas Sanders, based in the opulent St. Lawrence Hotel in Montreal, where mint juleps were served year-round to Confederates living in Canada, led the crusade to influence and control "the Democracy," the Democratic Party’s self-aggrandizing term for itself at the time.

The full story of this clandestine organization and its covert operations is told in my bestselling book, "The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations."

The book reveals the drama of the irregular guerrilla warfare that altered the course of the Civil War, including the story of President Abraham Lincoln’s special forces who donned Confederate gray to hunt John Singleton Mosby and his Confederate Rangers from 1863 to the war’s end at Appomattox.

It's a previously untold story that inspired the creation of U.S. modern special operations in World War II, and also goes into the story of the Confederate Secret Service. The book gives a groundbreaking, fresh perspective on the Civil War.

Piratical, fat and restless, George Sanders, a savvy covert warrior and diplomat who advocated the assassination "Theory of the Dagger" or killing what he considered to be unjust leaders, keenly understood information warfare and the power of the media.

He bragged to Davis that his next goal was "the Democracy [the Democratic Party] having possession of the press." Among other initiatives, the Secret Service, according to one Confederate operative, sent tens of thousands of dollars to various Democrat news organizations.

Much of the Northern press was virulently anti-war and anti-Lincoln, and the articles had a chilling effect as they sapped Northern morale. Accordingly, the Confederate Secret Service plied Northern newspapers with cash to shape the Confederacy’s narrative of how hopeless and fruitless the war had become.

Horace Greeley, the influential editor of the New York Tribune, was an antislavery crusader who supported the war but was horrified by its aftermath and the stalled Union offensives that seemed to go nowhere – a forever war.

He summed up the mood of the country in writing to Lincoln, "Nine-tenths of the whole American people, North and South, are anxious for peace — peace on almost any terms — and utterly sick of human slaughter and devastation."

In a master stroke in the summer of 1864, Sanders and the Secret Service set up a phony peace conference to trick Lincoln into admitting the war would not end until the Confederacy surrendered, and slavery was abolished.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

The scheme worked, and Sanders quickly shot off a press release to the Associated Press, which ran it on their wire, "All the Democratic press denounce Lincoln’s manifesto in strong terms, and many Republican presses admit it was a blunder." The Democratic platform for 1864, which the Confederate Secret Service would help write, called for an armistice and the continuation of slavery.

As the Twentieth Century and first quarter of this century have proven, insurgencies are almost impossible to destroy if they have the support of the population. The South did not have to win the war but merely survive it.

By 1864, much of the South’s vast territory had not been occupied by Northern troops, and the Southern people were overwhelmingly supportive of the war. Occupying the entire South against a hostile American population was nearly impossible as the British had fruitlessly attempted decades earlier in The Revolution and The War of 1812.

Controlling the narrative through an information war to influence hearts and minds became central in the Confederacy’s shadow war. In the summer of 1864, Northern armies were forced to retreat at Lynchburg, Virginia, and Confederate General Jubal Early’s army marched through the Shenandoah Valley and nearly seized Washington, D.C.

Hundreds of thousands of Union soldiers lay dead as casualties, and desertions in the Union skyrocketed. Through the Confederate Secret Services’ efforts, the press magnified the despair and the belief that a political solution was needed to end the forever war.

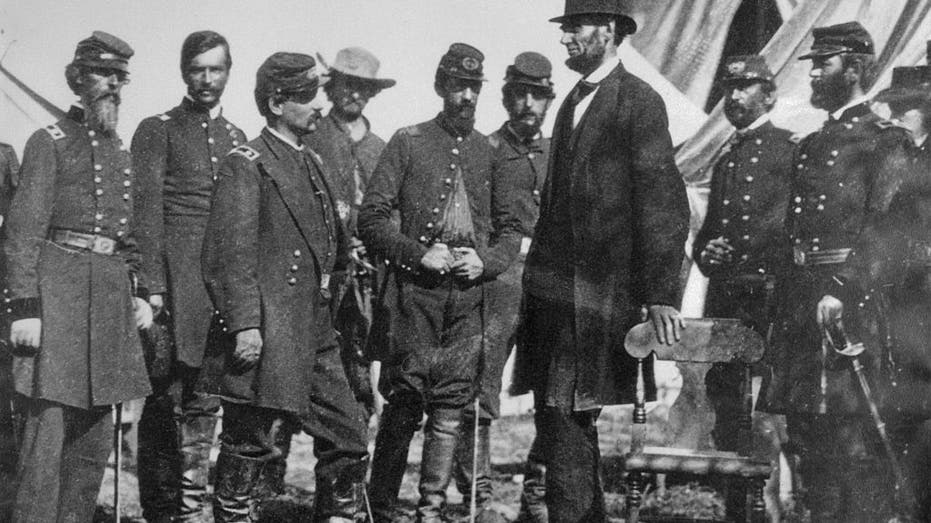

As the Chicago Democratic Convention in August 1864 loomed, "The Democracy" was ascendent in the polls. A despondent President Abraham Lincoln, wrote, "You think I don’t know I am going to be beaten, but I do, and unless some great change takes place, I will be badly beaten."