How to Pick a New Democratic Presidential Candidate Fast

Get the leaders together and make a choice.

One paradox of the Democratic Party’s crisis is that most people agree it has to do something, but there’s little consensus on what that something would be. If you assume first that President Biden should drop out of the race (I’m a definite yes) and second that he will (maybe? Probably?), the options all have novel risks.

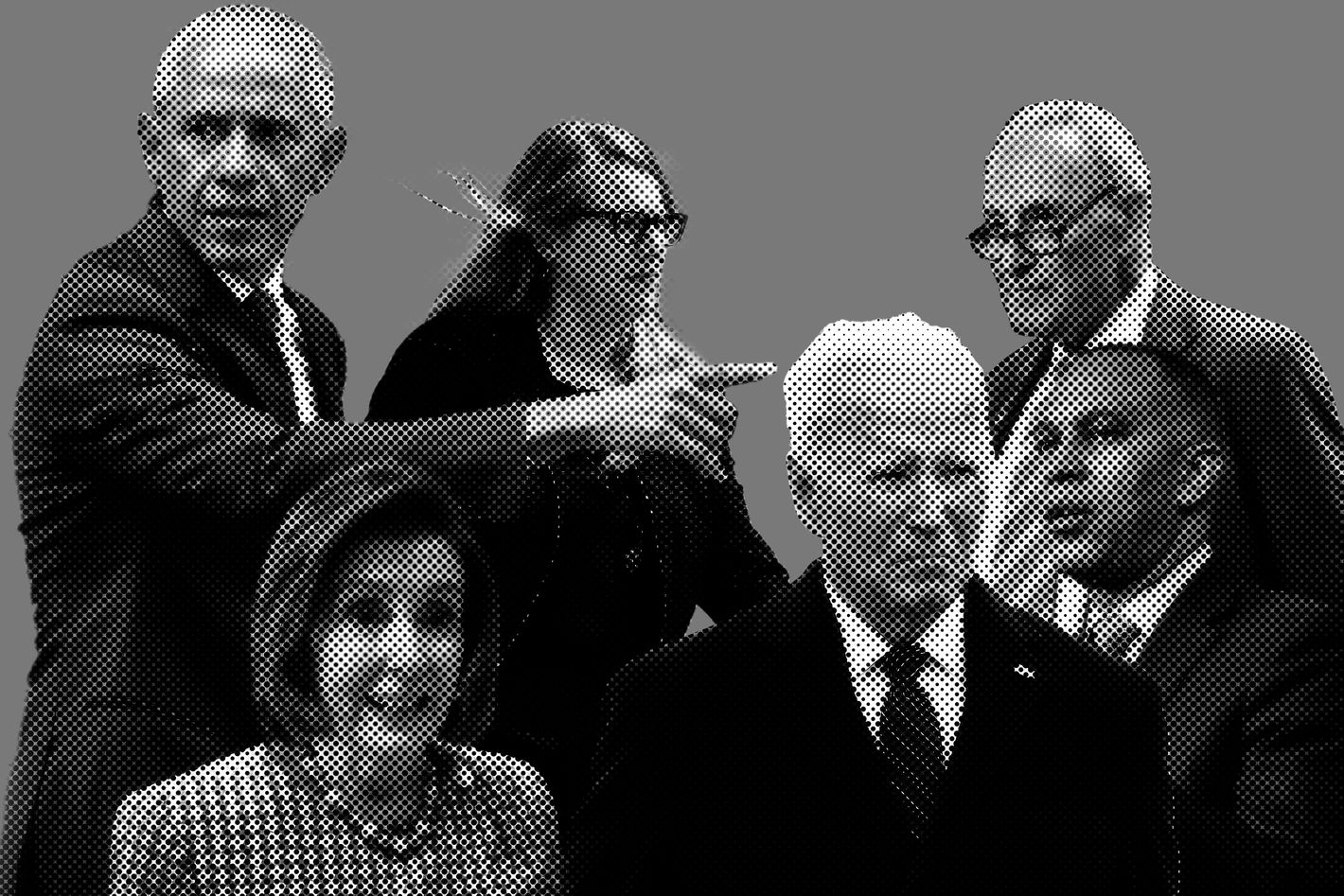

Here, with the trepidation and uncertainty befitting a fast-moving and unprecedented situation, is what I think should happen. A small group of party leaders — say, Biden, Barack Obama, Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, Hakeem Jeffries, and Jen O’Malley Dillon — should decide on a new candidate over the next week. The group would present its choice and instruct delegates to ratify the nomination at the convention.

The most common views on finding a replacement are either that Biden should simply tap Kamala Harris or that he should throw the decision to an open convention. The arguments for both these choices flow from the misplaced idea that the most important factor in picking the nominee is maintaining unity among Democratic partisans. I believe, to the contrary, the most important thing is to find a candidate who can appeal to voters outside the Democratic Party’s base.

The case for Harris is that failing to select her is “the political optics of a fight that would imperil support from Black voters and women,” as NBC put it. The case for a convention implicitly assumes the nominee may not be Harris and reasons that the process of picking somebody else needs to be open and legitimate and that a period of campaigning followed by voting in Chicago would fulfill this.

A party’s base, by definition, consists of people who are going to vote for it no matter what. The base lacks leverage precisely for this reason, which is why so much rhetorical effort always goes into inflating its importance. Both parties have permanent infrastructures of activist groups who insist the party must endorse their preferred policies or candidates in order to energize the base or else the base will be demoralized.

Sometimes a base can be galvanized through sheer force of personality or circumstance. But usually choices that energize the base reduce the party’s chances of winning. In 2012, Mitt Romney decided not to simply run as an economic fixer focused on the slow recovery and instead center the election on the conservative plan to reduce taxes and retirement benefits. “It was a choice intended to galvanize the Republican base and represented a clear tactical shift by Mr. Romney, who, until now, had been singularly focused on weak job growth since Mr. Obama took office,” the New York Times reported. And indeed, the base was thrilled. “The Republican presidential ticket is drawing huge and at times electric crowds, at long last energizing a conservative base that has hungered for an inspiring standard-bearer,” observed the Washington Post.

If he kept his distance from the Paul Ryan plan, Romney might have lost anyway. But making it the center of his campaign, as conservatives demanded and held out as his salvation, all but ensured defeat.

“Harris could energize Democratic-leaning groups whose enthusiasm for Biden has faded — Black voters, young people and women,” speculates the Washington Post. It is certainly true that Biden needs to increase his support among Black voters and others. But the Black voters the Democrats need to win over are mostly moderates and conservatives who have little investment in Harris’s success (which is why they’re not currently planning to vote for the Biden-Harris ticket).

Threats that the party must satisfy demands from hard-core partisans are a tactic to manufacture artificial leverage. The idea of holding an open convention to pick a candidate is in part a response to these demands. It posits that activists will refuse to accept a nomination — except, perhaps if it’s Harris — unless that nomination is conferred through a regulated and quasi-transparent process. Congressman James Clyburn has proposed a “mini-primary.”

I wouldn’t go so far as to call an open convention unworkable. But it means by delaying the final selection for weeks in which the Democratic Party lacks a candidate, its main message consists of Democrats tearing each other down. And it creates a long period of time in which activists will be incentivized to ramp up their demands for their preferred candidate and platform, without being long enough to test the retail campaign skills of a candidate.

An open convention is supposed to be more democratic, and in some ways it would be. But in other ways it would give more leverage to activists whose preferences lie pretty far from those of rank-and-file Democrats, let alone the decisive persuadable voters who aren’t reliable Democrats.

The advantage of picking a candidate quickly through committee is that it can present the choice as a fait accompli. Maybe the choice will be Harris. If it’s not, that’s a sign high-level Democrats have serious reservations about her ability to campaign or govern, and we should take those reservations seriously. If it is Harris, that’s also a signal of confidence we should take seriously.

And when a choice is named, then fighting to overturn it becomes very costly. Some Democrats would certainly complain about it. But the overwhelming impetus would be to unify quickly and start campaigning against Donald Trump. The leverage being created by groups speaking for the base, or claiming to, dissolves when a selection has been announced.

It’s possible, of course, for a party’s base to fracture. But if you’ve lost your base, you’ve lost the election. A winning strategy needs to presuppose the likely outcome that high-turnout partisan voters will turn out for whoever the nominee is and find a candidate who can get the voters the party needs to beat Trump.