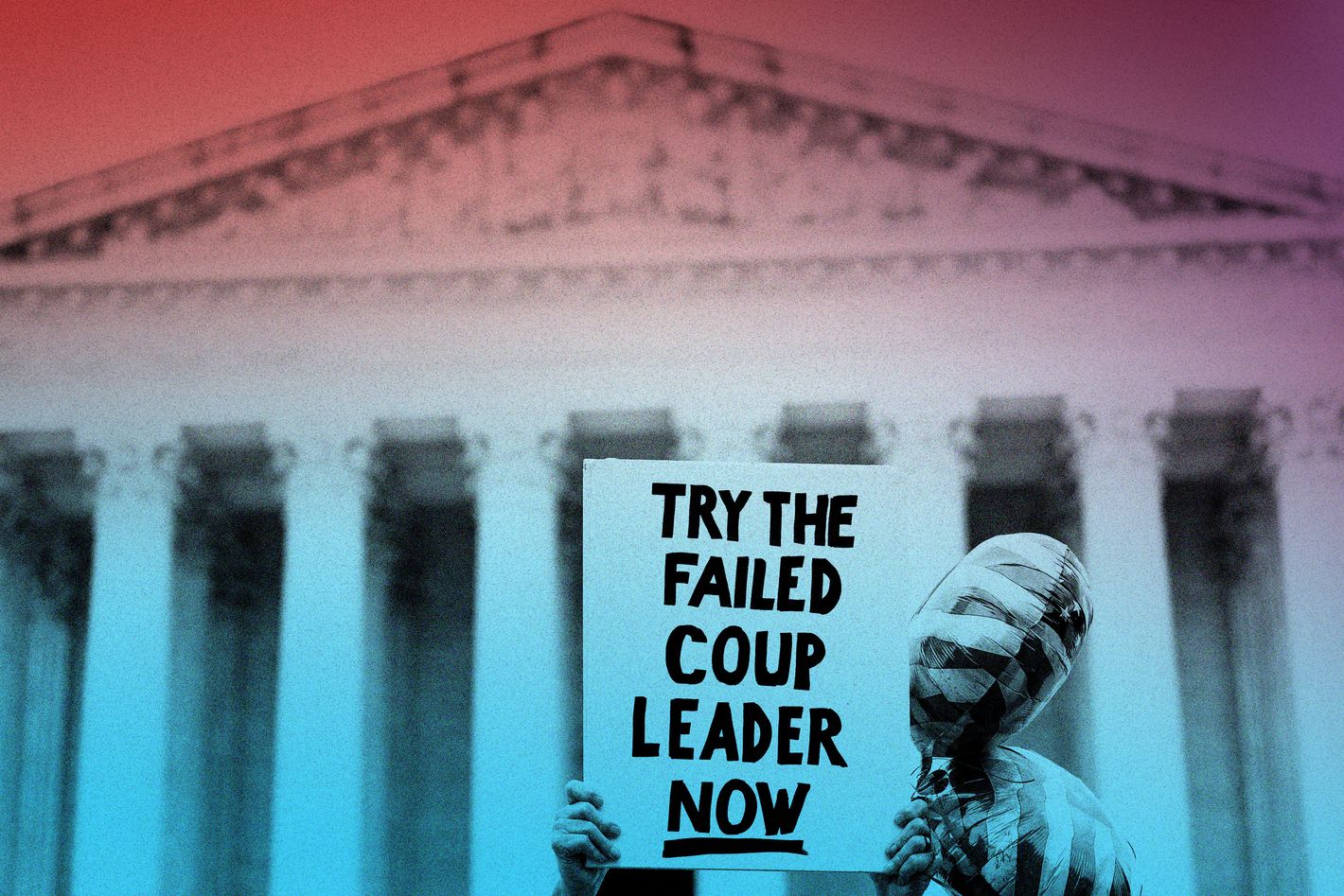

Did the Supreme Court Kill Every Case Against Trump?

Law professor Steve Vladeck on where a radical ruling leaves the former president’s prospects in court.

Last week, the Supreme Court handed Donald Trump a huge win when it ruled that current and former presidents could not be criminally prosecuted for acts deemed “official.” The 6-3 decision means further delays in federal government’s January 6 case, headed by Special Counsel Jack Smith. But the ruling is already having broader effects. Trump’s lawyers cited it in a successful request to delay their client’s sentencing in the New York hush-money case. His lawyers again cited the immunity decision when they requested that Judge Aileen Cannon, who oversees the federal classified-documents case against Trump, put those proceedings on hold altogether. (Even if that tactic fails, it has already resulted in yet another Cannon-approved delay.) There is surely more of this to come, in these and other Trump-involved cases.

I recently spoke with Steve Vladeck, a University of Texas law professor and CNN Supreme Court analyst, about how the Court’s ruling may affect Trump’s remaining trials and his concerns on how the decision could embolden a future president.

Trump’s legal team succeeded in getting Judge Juan Merchan, who is overseeing Trump’s hush-money case, to push back his scheduled sentencing by months, and they want Merchan to overturn the conviction altogether. Could the Supreme Court ruling open the door to that?

There’s a remote possibility; I think it’s unlikely. But I think the impact on the January 6 case is going to be substantial.

Where do you think things now stand with the January 6 case?

I think a lot is going to depend on the special counsel. Jack Smith and his team are super-savvy, and they’re parsing the ruling even more than we are. I think the question is, Are they going to try to restructure the case? Are they going to file a superseding indictment? Are they going to do other things to try to mitigate the need to resolve some of the hard questions the Supreme Court’s decision leaves open? And in that respect, the ball is very much in their court.

The Georgia election-subversion case deals with similar issues as the federal government’s but on the state level. If the federal case is severely curtailed or even thrown out entirely, could it affect what happens in Georgia?

At least to a degree. The Georgia case is different in some respects: Trump’s not the only defendant; the charges have involved a whole bunch of state law. I think it’s a straighter line in the Georgia case to stuff that’s clearly not an official act of the president. Calling the Georgia secretary of state and asking him to find 11,000 votes is not a presidential act. I think the problem really is that there’s no way to be confident in any direction in any of these cases about what the effects are going to be. It’s going to be a lot of uncertainty all the way down.

The federal government’s classified-documents case was already up in the air thanks to Judge Aileen Cannon, who has set a slow pace and made a series of strange pro-Trump rulings. Now, she’s facing this immunity argument Trump’s team is making. Is there a scenario in which she could toss the case by arguing that Trump’s handling of the documents was an official act, even though he was out of office by that time?

I don’t think that’s a good argument, but I think it’s an argument that will be made. Judge Cannon has shown herself to be open to arguments that are not necessarily good. There’s also Justice Thomas’s concurrence, which has not gotten a lot of attention. There’s a motion before Judge Cannon raising the exact unconstitutional appointment argument that Justice Thomas embraced in his concurrence. I think the reverberations of this decision are going to be widely felt and are going to take a fairly long period of time to fully sort themselves out.

Right. In his opinion, Clarence Thomas questioned the legality of Smith’s appointment in the first place. Cannon was already set to hold a hearing on that very subject. Could Smith’s position be at risk?

The fact that it was only Thomas should give folks pause about this argument, which I think is a completely meritless one. But if Cannon relies upon it, then she could rule that Smith’s appointment was unconstitutional, which Smith would obviously then appeal.

The Supreme Court’s jurisprudence is quite clear that the special counsel is something called an “inferior officer,” not a principal officer. Congress, by statute, has authorized the attorney general to appoint inferior officers. Unlike in the case of the independent counsel, the special counsel is directly answerable to the attorney general. And so, even for those who think the Supreme Court’s decision upholding the independent-counsel statute was wrong, this is radically different. There’s a 2019 ruling by the D.C. Circuit expressly rejecting this very challenge in the context of the appointment of then–Special Counsel Bob Muller. The overwhelming weight of authority is against this argument as reflected in the fact that only one justice endorsed it. But that’s no guarantee that Judge Cannon will feel bound to reject it.

What stuck out to you about the Supreme Court’s ruling when it first came down?

I was struck by two things. I was struck that the Court wasn’t able to find any kind of cross-ideological consensus, which historically in cases like this has really been one of its principal goals. And I was struck by the point of departure between the majority and Justice Barrett, specifically the majority’s — to me — completely unjustified and problematic holding that even when the underlying crime can be tried, otherwise immunized conduct can’t even be used as evidence. I think it says a lot about how extraordinary and extreme that holding was that Justice Barrett felt compelled to write separately to say she didn’t agree with it.

Is it unusual that Amy Coney Barrett would feel the need to put that on the record, so to speak?

Unusual except that she did the same thing in the Colorado ballot-disqualification case, where she also was slightly critical of the five other Republican appointees for going further than she thought was necessary. Wholly apart from the legal analysis, which is problematic unto itself, it really drives home just how much further the majority went than it needed to.

There has been a lot of discussion on what makes something an official act versus an unofficial one. How are you looking at this question?

I think that’s going to be hard but not intractable. Lower courts sometimes actually do confront similar questions, with lower stakes, about official versus nonofficial conduct. I’m much more worried about the evidentiary point because I just don’t understand how prosecutors are supposed to establish the difference between an act being official and unofficial if their hands are so thoroughly tied with regard to what evidence they are or aren’t allowed to introduce.

So it’s not that the ruling explicitly allows these things but that it muddies the waters a bit.

It muddies the waters a lot.

It removes this guardrail that everyone assumed existed, that any president would be subject to the law.

“Removes the guardrail” is strong. It certainly lowers the guardrail. The lower the guardrail, the easier it’s going to be for presidents to drive off the road.

In her dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor put forward several scenarios in which she worries a future president could be immune under this ruling. These include giving a pardon in exchange for a bribe or using Seal Team Six to assassinate a political rival, which came up at oral arguments. From your perspective, are these things now legal for a president to do?

It’s impossible to disagree with her concern. I think the problem with assessing each of her hypotheticals is that the majority’s opinion isn’t clear. And so the concern to me is not that it’s obvious a president would be immune in those cases; it’s that it’s not obvious he wouldn’t be.

What else are you looking for in how this ruling may reverberate down the line?

I think the problem is that this rule is going to have two sets of reverberations: It’s going to have short-term reverberations in somewhere between one and four of the Trump prosecutions, and it’s going to have long-term reverberations for the entire structure of our federal government and the ways in which we do and don’t hold presidents accountable. The problem is that it’s just impossible to say this early whether those reverberations are going to be good or bad. I’ll just say I’m worried that they’re going to be bad, but only time will tell.

What is the worst-case scenario for a second Trump term or any future presidency?

The real concern here is what this ruling will incentivize or at least what this ruling will fail to deter. Whether it’s a second Trump administration or a second Biden administration or an anybody else administration, presidents ought to be at least somewhat worried that if they break the law, they’ll be held accountable. And given how feckless the impeachment process has shown itself to be, it’s not obvious how any future president acting in good faith or bad would actually be worried about being held to account for breaking the law.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.