The Catholic Church in China Has Been Co-Opted by the Communist Party

Nestled among the three thousand or so engraved slabs and columns that make up the city of Xi’an’s sprawling Stele Forest, in the second of the seven galleries devoted to Confucian, calligraphic, poetic, and all other manner of ancient stelae,...

The post The Catholic Church in China Has Been Co-Opted by the Communist Party appeared first on The American Spectator | USA News and Politics.

Nestled among the three thousand or so engraved slabs and columns that make up the city of Xi’an’s sprawling Stele Forest, in the second of the seven galleries devoted to Confucian, calligraphic, poetic, and all other manner of ancient stelae, rests one of the most astonishing artifacts in all of China. It is the daqin jingjiao liuxing zhongguo bei (大秦景教流行中国碑), or the Stele to the Propagation in China of the Luminous Faith of the Roman Empire, usually referred to simply as the jingjiao bei, or the Stele of the Luminous Faith. Rising to a considerable height of nine feet, and inscribed from top to bottom with 1,900 Chinese characters and a smattering of Syriac text, the stele was erected on January 7, 781, in the Tang imperial capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an), to commemorate the first arrival of Christians in China, who brought with them a “luminous faith” characterized by the worship of Allaha and Mshiha, the Syriac words for God and Christ that were phonetically transcribed into Chinese and carved into the surface of the immense black limestone block.

Subscribe to The American Spectator to receive our latest print magazine, which includes this article and others like it.

According to the stele inscription: “Among the enlightened and holy men who arrived was the most-virtuous Olopun, from the country of Syria. Observing the azure clouds, he bore the true sacred books; beholding the direction of the winds, he braved difficulties and dangers, and in the year 635 he arrived at Chang’an.” Owing to the efforts of Olopun and his fellow proselytizers, Christian communities took root in Tang China, where they were welcomed by the broad-minded Emperor Taizong, whose own syncretic personal religion borrowed liberally from Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Islam, Christianity, and other Eurasian religions. Sadly, this atmosphere of religious tolerance and coexistence did not last, and, in 845, the beleaguered and immortality-obsessed Emperor Wuzong launched a campaign to eradicate Buddhism, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and indeed everything other than indigenous Confucianism and Taoism from the Middle Kingdom. In 987, the Nestorian scribe Abul-Faraj would recall meeting a Chinese monk passing through Baghdad who lamented, “Christianity was just extinct in China; the native Christians had perished in one way or another; the church which they had used had been destroyed; and there was only one Christian left in the land.” That last Christian was presumably the monk himself.

This article is taken from The American Spectator’s latest print magazine. Subscribe to receive the entire magazine.

Jingjiao, China’s luminous faith, did not die out, however, and the sixteenth-century appearance of the Jesuits, led by Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci, heralded a new dawn. These missionaries cleverly employed a strategy of culturally sensitive accommodation, treating Chinese civilization as equal to that of Europe and drawing parallels between classical Chinese and Christian texts. The result was a glorious syncretism. I can think of no music more beautiful than the divertissements chinoises composed by the Baroque organist Teodorico Pedrini, who was dispatched by the Vatican to the Forbidden City to serve as a music tutor for the Kanji emperor’s three sons. And I can think of few paintings more captivating and intriguing than the Ming-era Madonna Scroll in the Field Museum’s collection, with its depiction of the Virgin Mary looking rather like the Buddhist bodhisattva Guanyin, goddess of mercy, replete with a forged stamp of the renowned Ming artist Tang Yin, perhaps meant to confuse censors in the event of future religious persecutions. The achievements of Chinese Christianity are primarily measured not in artistic masterpieces, of course, but in souls, and by 1844, there were some 240,000 Chinese Catholics, a number that increased to around 720,000 in 1901, and to around six million today, alongside as many as thirty-eight million Protestants.

Christianity’s taproots in China plunge deep into the centuries, far deeper than the shallow epiphytes of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism.

Christianity’s taproots in China plunge deep into the centuries, far deeper than the shallow epiphytes of Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. When the Communists took power in 1949, they naturally looked askance at preexisting Christian communities, and, as the historian Daniel Bays noted, it was “not surprising that this new government, like the emperors of several dynasties of the last millennium, evinced an insistence on monitoring religious life and requiring all religions, for example, to register their venues and leadership personnel with a government office.” The Qing dynasty had at times lumped Christianity in with “wizards, witches, and all other superstitions” and interdicted the distribution of religious texts; the Communists would likewise alternate between suppressing and heavily regulating the Christian religion. During the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guards destroyed churches, murdered priests, and raped nuns. Post-Mao authorities employed a lighter touch, instead propping up the Three-Self Patriotic Movement, a supervisory organ for the Protestant communities, and the Catholic Patriotic Association, a state-managed church that, according to the 1950 Guangyuan Manifesto, is “independent in its administration, its resources, and its apostolate,” much to the Vatican’s chagrin. House churches and other forms of unregulated religious expression, meanwhile, remained illegal.

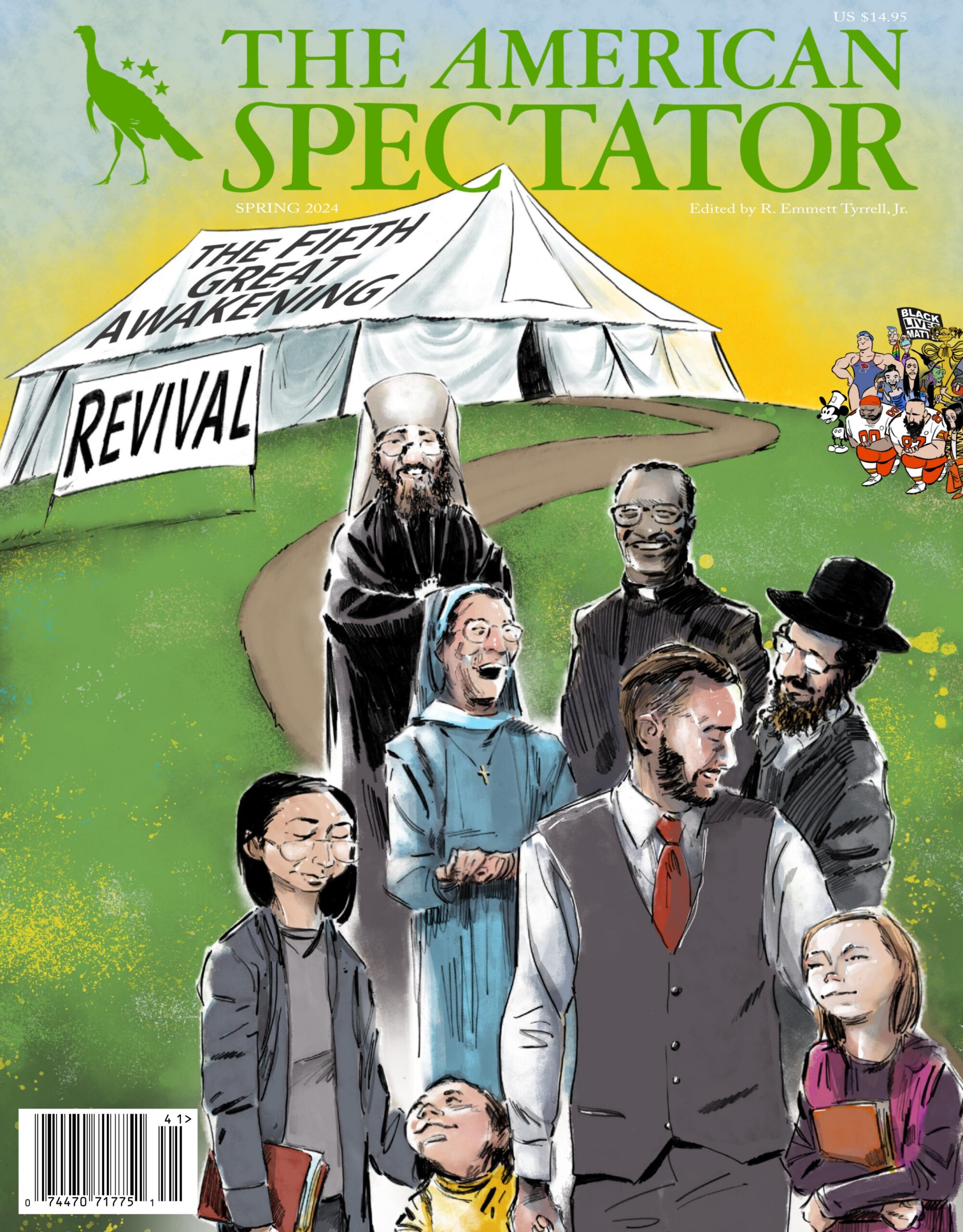

The American Spectator

Efforts to regulate and restrict Chinese religious life have only accelerated under the rule of Xi Jinping. The Chinese Communist Party exerts pressure on the five recognized religions (Taoism, Buddhism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism) to “Sinicize,” which really means adhering to a Patriotic Education Law that requires constant political indoctrination from the pulpit, lectern, or minbar. Unregistered churches are raided, sanctioned, draped with banners reading “Guide Religion With Core Socialist Values,” and then shuttered, while those caught in possession of illegally printed religious texts face jail time and crippling fines. The intensity of persecution is not on the level of the dark days of Emperor Wuzong, or the more recent Cultural Revolution, since the Party is content to absorb and neutralize these age-old religious institutions, as it anticipates a less contentious extinction event in the future.

The Holy See now finds itself in an unenviable position. The Chinese government exercises increasing control over the Catholic Patriotic Association while threatening faithful but unaffiliated Catholics with further oppression. In 2018, the Vatican and Beijing came to an accord, the contents of which are closely guarded. The agreement, which was renewed in 2020 and 2022, is meant to regularize the status of underground Catholics while legitimizing the Catholic Patriotic Association.

Art by Bill Wilson

Pope Benedict XVI had previously warned that “compliance with those authorities is not acceptable when they interfere unduly in matters regarding the faith and discipline of the Church,” particularly with respect to “forces that influence the family negatively,” with which Red China is positively awash. But the current Bishop of Rome has been more willing to seek rapprochement with Beijing, confusing the theological accommodation of his Jesuit forebears with the political accommodation (otherwise known as kowtowing) demanded by the ruthless apparatchiks of the Zhongnanhai. An unending humiliation ritual has been the result.

On November 25, 2022, Cardinal Emeritus Joseph Zen was found guilty by a Hong Kong court on a trumped-up charge of failing to register a humanitarian relief fund, just a day after Bishop Giovanni Peng Weizhao was installed as auxiliary bishop of Jiangxi, over the vociferous objections of the Vatican. A few months later, Bishop Shen Bin was installed as the bishop of Shanghai, again contrary to the wishes of the Holy See. As Bitter Winter’s Massimo Introvigne has argued: “[T]wo clues make a proof. It is now obvious that the Vatican-Chinese deal of 2018 is regarded by the CCP as binding for the Vatican only, which is expected not to criticize religious persecution in China, but not binding for Beijing, which appoints Catholic bishops as it deems fit, with or without Papal mandate.” And worse was still to come. On October 17, 2023, the Chinese Anti-Xie-Jiao Association, which combats so-called evil cults, provocatively republished a statement made twenty-two years earlier by Bishop Michael Fu Tieshan, then the head of the Catholic Patriotic Association. This statement described “genuine religions” as “progressive” and “enthusiastic” about the Communist Party and contrasted them with “cults” like Falun Gong, which are “ugly,” “trample on human ethics,” “destroy human nature,” and pose “a threat to society.”

Catholicism been co-opted by the communist government as part of a bloody campaign of religious persecution, murder, and organ harvesting.

Thus has Catholicism been co-opted by the communist government as part of a bloody campaign of religious persecution, murder, and organ harvesting, without the slightest pushback from the Catholic Patriotic Association or the Vatican. Chinese Catholics find themselves in an increasingly untenable situation.

No Christian of good conscience should be obliged to pledge fidelity to such an ersatz church, yet the only alternatives are joining precarious underground communities, as in the time of Nero or Diocletian, or quietly consuming contraband religious texts and listening to audio Bible players preloaded with gospel verses and hymns, in direct contravention of draconian laws against “illegal publications and pornography.”

The Vatican’s secret pact with the Chinese government has been violated repeatedly and brazenly, but it remains to be seen whether Pope Francis — who as recently as September 4, 2023, characterized Sino-Vatican relations as “very respectful” — is willing to trigger a confrontation between the two global titans, one spiritual, the other political. The Holy See would do well to remember, as the Catholic philosopher Nicolás Gómez Dávila so eloquently maintained, that “[T]he Church’s function is not to adapt Christianity to the world, nor even to adapt the world to Christianity; her function is to maintain a counter-world in the world.” That counterworld arrived in China 1,389 years ago, conveyed there, as the Xi’an Stele informs us, “by enlightened and holy men” who “braved difficulties and dangers” in the service of Christ and the jingjiao, the “luminous faith.” This year figures to be a crucial one in the history of Chinese Catholicism, which has survived for far too long, in the face of so many persecutions and cultural revolutions, to be condemned to a lingering and inglorious demise by genocidal communists and credulous prelates.

Subscribe to The American Spectator to receive our latest print magazine on the future of religion in America.

Matthew Omolesky is a human rights lawyer, a researcher in the field of cultural heritage preservation, and a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute.

The post The Catholic Church in China Has Been Co-Opted by the Communist Party appeared first on The American Spectator | USA News and Politics.