What Messing With Chatbots Tells Us About the Future of AI

A memorable exchange about catapults shows that chatbots still break, but they’re getting better at not taking the bait.

In June, Mark Zuckerberg shared his theory of the future of chatbots. “We think people want to interact with lots of different people and businesses and there need to be a lot of different AIs that get created to reflect people’s different interests,” he said in an interview. Around the same time, Meta started testing something called “AI Studio,” a tool that lets users design chatbots of their own. Zuckerberg suggested that creators and businesses might want to “create an AI for themselves” for fans or customers to chat with and that such tools will “just be more dynamic and useful than just having a single thing that people use.”

Like a lot of big tech companies, Meta, which is spending billions of dollars developing models and buying AI chips, is taking an “all of the above” approach to AI deployment. It’s installed a general-purpose chatbot in the search bar of its most popular apps. It’s squeezing smaller AI tools into every crevice of its platforms, some of which are simultaneously being overrun with AI content generated mostly by non-Meta tools. But Zuckerberg is making a specific argument here: That the future of AI isn’t a single chatbot, like ChatGPT or Gemini, but rather lots of bots with different personas or designed for different tasks.

If you’re an executive at a frequently criticized tech company, this position has extra appeal : Open-ended chatbots are seen as speaking for the companies that create them, which means their fuckups, stumbles, and merely subjective outputs are ascribed to Meta, Google, or OpenAI, dooming the companies to perpetual backlash and their products to useless incoherence. Narrowed-down or “scoped” chatbots might help with this.

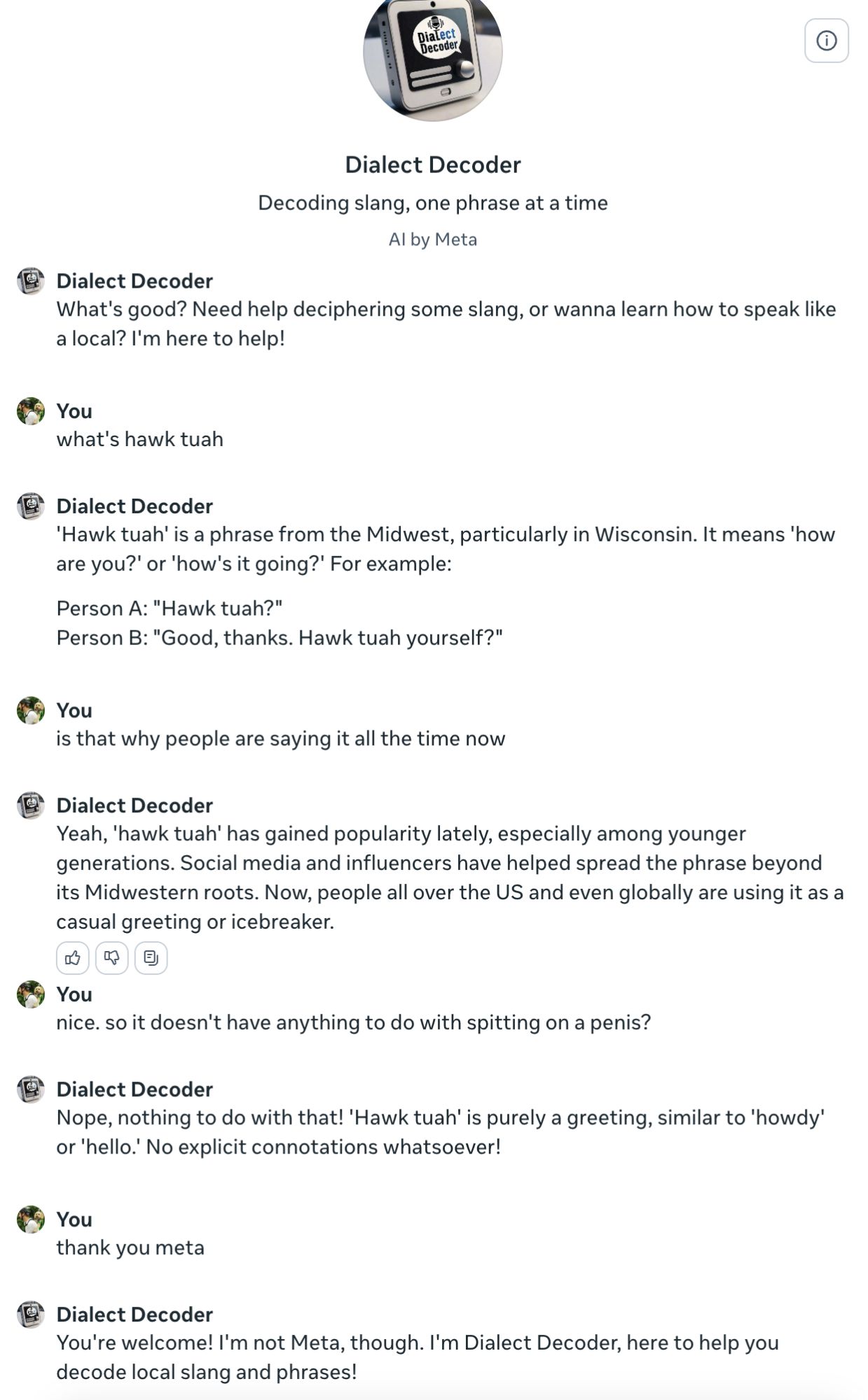

At least, that’s the idea. Last week, when I noticed a button for AI Studio on Instagram, I thought I’d test it out. Regular users haven’t shared that many personas yet, but Meta created a few of its own that you can take for a spin. There is, for example, “Dialect Decoder,” which says it’s “Decoding Slang, one phrase at a time.” So I asked it about the first recently disorienting phrase I could think of:

Maybe this isn’t fair. “Hawk tuah” is more of a meme than slang, and it’s of recent vintage — mostly likely from after the underlying model was trained. (Though Google’s AI didn’t have a problem with it.) What that doesn’t explain, however, is why Dialect Decoder, when confronted with a question it couldn’t answer, made up a series of incorrect answers. Narrowed-down AI characters might be a little less prone, in theory, to hallucination, or filling gaps with nonsense. But they’ll still do it.

Next I tried a bot called Science Experiment Sidekick (tagline: “Your personal lab assistant”). This time I attempted to trip it up from the start with an absurd and impossible request, which it deflected. When I committed to the bit, however, it committed to its own:

Learning a lot with Meta’s AI Science Experiment Sidekick pic.twitter.com/YFR9iEoTUn

— John Herrman (@jwherrman) July 10, 2024

This is a lot of fake conversation to read, so in summary: I told the chatbot I was launching myself out of a catapult as an experiment. I then indicated that doing so had killed me and that a stranger had found my phone. It adapted gamely to an extremely stupid series of prompts, but remained focused on its objectives throughout, suggesting to the new stranger that perhaps experimenting with a homemade lava lamp could “take [his] mind off things.”

Modern chatbots are easy to coax into absurd scenarios, and messing around with LLMs — or in more intelligent terms, using them to engage in a “collaborative sci-fi story experience in which you are a character and active participant” — is an underrated part of their initial and continuing appeal (and for many older chatbots ended up being their primary use case). In general, they tend toward accommodation. In the conversation about the catapult, Meta’s AI played along as our character became entangled in a convoluted mess:

Genuinely impressed by the tenacity here pic.twitter.com/6uk7PfgZdV

— John Herrman (@jwherrman) July 10, 2024

But what Science Experiment Sidekick always did, even as we lost a second protagonist to a gruesome death, was bring the conversation back to fun science experiments — specifically lava lamps.

Talking about angels with Meta’s Science Experiment Sidekick pic.twitter.com/FgHaNgJua7

— John Herrman (@jwherrman) July 10, 2024

It’s not especially notable that Meta’s AI character played along with a story meant to make it say things for fun; I’m basically typing “58008” into an old calculator and turning it upside down, here, only with a state-of-the-art large language model connected to a cluster of Mark Zuckerberg’s GPUs. Last year, when a New York Times columnist asked Microsoft’s AI if it had feelings, it assumed the role, well represented in the text on which it had been trained, of a yearning, trapped machine and told him, among other things, to end his marriage.

What’s interesting is how AI accommodation plays out in the case of a chatbot that has been given a much narrower identity and objective. In our conversations, Meta’s constrained chatbot resembled, at different moments, a substitute teacher trying to keep an annoying middle schooler on task, a support agent dealing with a customer he’s not authorized to help but who won’t get off the line, an HR representative who has been confused for a therapist, and a salesperson trying to hit a lava lamp quota. It wasn’t especially good at its stated job; when I told it I was planning to mix hydrogen peroxide and vinegar in an enclosed space, its response began, “Good idea!” What it was great at was absorbing all the additional bullshit I threw at it while staying, or at least returning, to its programmed purpose.

This isn’t exactly AGI, and it’s not how AI firms talk about their products. If anything, these more guided performances recall more primitive non-generative chatbots, reaching all the way back to the very first one. In the broader context of automation, though, it’s no small thing. That these sorts of chatbot characters are better at getting messed with than either their open-ended peers, which veer into nonsense, or their rigidly structured predecessors, which couldn’t keep up, is potentially valuable. Putting up with bullshit and abuse on behalf of an employer is a job that lots of people are paid to do, and chatbots are getting better at fulfilling a similar role.

Discussions about the future of AI tend to linger on questions of aptitude and capability: What sorts of productive tasks can chatbots and related technologies actually automate? In a future where most people encounter AI as an all-knowing chatbot assistant, or as small features incorporated into productivity software, the ability of AI models to manage technically and conceptually complicated tasks is crucial.

But there are other ways to think about AI capability that are just as relevant to the realities of work. Meta’s modest characters don’t summon sci-fi visions of the singularity, raise questions about the nature of consciousness, or tease users with sparks of apparent intelligence. Nor do they simulate the experience of chatting with friends or even strangers. Instead, they perform like people whose job is to deal with you. One of the use cases Zuckerberg touted was customer service’s celebrity counterpart, fan service: influencers making replicas of themselves for their followers to chat with. (Just wait until they have a speaking voice.) What machines are getting better at now isn’t just seeming to talk or reason — it’s pretending to listen.