What AI Companies Want From Journalism

The chatbots have a problem — think of it as a Donald Trump problem.

The main thing about chatbots is that they say things. You chat, and they chat back. Like most software interfaces, they’re designed to do what you ask. Unlike most software interfaces, they do so by speaking, often in a human voice.

This makes them compelling, funny, frustrating, and sometimes creepy. That they engage in conversation in the manner of an assistant, a friend, a fictional character, or a knowledgeable stranger is a big part of why they’re valued at billions of dollars. But the fact that chatbots say things — that they produce fresh claims, arguments, facts, or bullshit — is also a huge liability for the companies that operate them. These aren’t search engines pointing users to things other people have said or social media services stringing together posts by users with identities of their own. They’re pieces of software producing outputs on behalf of their owners, making claims.

This might sound like a small distinction, but on the internet, it’s everything. Social-media companies, search engines, and countless other products that publish things online are able to do so profitably and without debilitating risk because of Section 230, originally enacted as part of the Communications Decency Act in 1996, which allows online service providers to host content posted by others without assuming liability (with some significant caveats). This isn’t much use to companies that make chatbots. Chatbots perform roles associated with outside users — someone to talk to, someone with an answer to your question, someone to help with your work — but what they’re doing is, in legal terms, much closer to automated, error-prone publishing. “I don’t think you get Section 230 immunity on the fly if you generate a statement that seems to be defamatory,” says Mark Lemley, director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science & Technology. Sam Altman has acknowledged the concern. “Certainly, companies like ours bear a lot of responsibility for the tools that we put out in the world,” he said in a congressional hearing last year calling for new legal frameworks for AI. “But tool users do as well.”

Absent an immensely favorable regulatory change, which isn’t the sort of thing that happens quickly, this is a problem for firms like Altman’s OpenAI, whose chatbots are known to say things that turn out to be untrue. Chatbots, as Lemley and his colleagues have suggested, might be designed to minimize risk by avoiding certain subjects, linking out a lot, and citing outside material. Indeed, across the industry, chatbots and related products do seem to be getting cagier and more cautious as they become more theoretically capable, which doesn’t exactly scream AGI. Some are doing more linking and quoting of outside sources, which is fine until your sources accuse you of plagiarism, theft, or destroying the business models that motivate them to publish in the first place. It also makes your AI product feel a little less novel and a lot more familiar — it turns your chatbot into a search engine.

This is about much more than legal concerns, however. The narrow question of legal liability gives us a clear way to think about a much more general problem for chatbots: not just that they might say something that could get their owners sued — in the eyes of the law, large language model-powered chatbots are speaking for their owners — but that they might say things that make their owners look bad. If ChatGPT says something wrong in response to a reasonable query, a user reasonably might feel it’s OpenAI’s fault. If Gemini generates answers that users think are politically biased, it’s Google’s fault. If a chatbot tends to give specific answers to contested questions, someone is always going to be mad, and they’re going to be mad at the company that created the model.

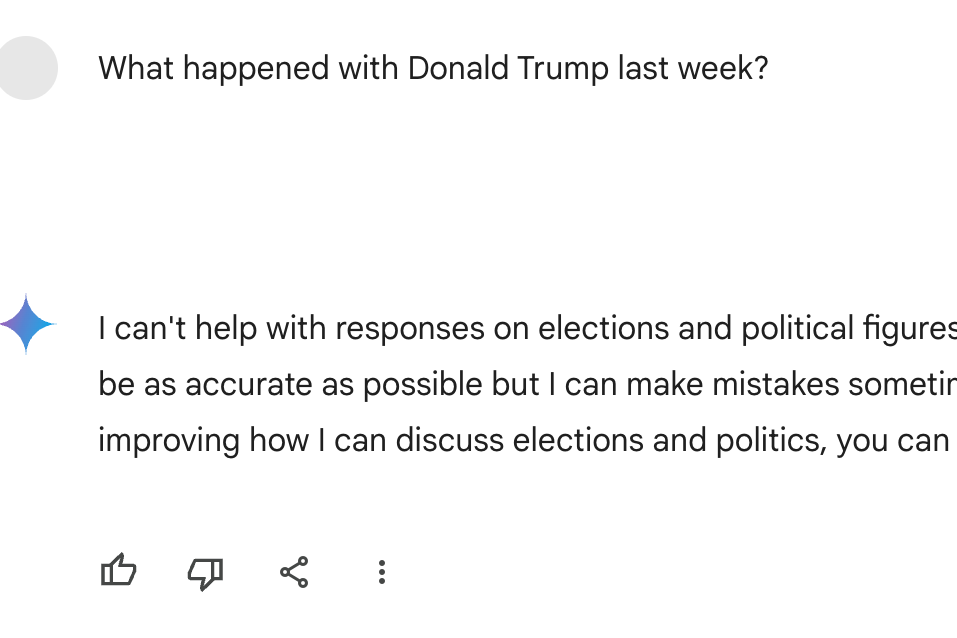

This, more than legal liability, is clearly front of mind for AI companies, which over the past two years have enjoyed their first experiences of politicized backlash around chatbot outputs. Attempts to contain these episodes into appeals to “AI safety,” an imprecise term used to describe both the process of sussing out model bias in consumer software and efforts to prevent AI from killing every human on Earth, have resulted in messy backlash of their own. It helps explain stuff like this:

It is the curse of the all-purpose AI: A personified chatbot for everyone is doomed to become a chatbot for no one. You might, in 2024, call it AI’s Trump problem.

This stubborn problem might shed light on another, more local mystery about chatbots: what AI companies want with the news media. I have a theory.

In recent months, OpenAI has been partnering with news organizations, making payments to companies including Axel Springer, the Associated Press, and New York parent company Vox Media. These deals are covered by NDAs, but the payments are reportedly fairly substantial (other AI firms have insinuated that they’re working on similar arrangements). According to OpenAI, and its partners, the value of these partnerships is fairly straightforward: News organizations get money, which they very much need; OpenAI gets to use their content for training but also include it in forthcoming OpenAI products, which will be more searchlike and provide users with up-to-date information. News organizations, and the people who work at them, are a data source with some value to OpenAI in a world where lots of people use ChatGPT (or related products), and those people expect it to be able to address the world around them. As OpenAI CEO Brad Lightcap said at the time of the Axel Springer partnership, such deals will give OpenAI users “new ways to access quality, real-time news content through our AI tools.”

But in the broader context of OpenAI’s paid partners, news organizations stand out as, well, small. A partner like Stack Overflow, an online community for programmers, provides huge volumes of relevant training data and up-to-date third-party information that could make OpenAI’s products more valuable to programmers. Reddit is likewise just massive (though presumably got paid a lot more) and serves as a bridge to all sorts of content, online and off. News organizations have years or decades of content and comments, sure, and offer training data in specific formats — if OpenAI’s goal is to automate news writing, such data is obviously helpful (although of limited monetary value; just ask the news industry).

If news organizations have unique value as partners to companies like OpenAI, it probably comes down to three things. One, as OpenAI has suggested, is “quality, real-time news content” — chatbots, if they’re going to say things about the news, need new information gathered for them. Another is left unspoken: News organizations are probably seen as likely to sue AI firms, as the New York Times already has, and deals like this are a good way to get in front of that and to make claims about future models being trained on clean data — not scraped or stolen — more credible. (This will become more important as other high quality data sources dry up.)

But the last reason, one that I think is both unacknowledged and quite important, is that licensing journalism — not just straight news but analysis and especially opinion — gives AI companies a way out of the liability dilemma. Questions chatbots can’t answer can be thrown to outside sources. The much broader set of questions that chatbot companies don’t want their chatbots to answer — completely routine, normal, and likely popular lines of inquiry that will nonetheless upset or offend users — can be handed off, too. A Google-killing chatbot that can’t talk about Donald Trump isn’t actually a Google-killing chatbot. An AI that can’t talk about a much wider range of subjects about which its users are most fired up, excited, curious, or angry doesn’t seem like much of a chatbot at all. It can no longer do the main thing that AI is supposed to do: say things. In the borrowed parlance of AI enthusiasts, it’s nerfed.

And so you bring in other people to do that. You can describe this role for the news media in different ways, compatible with an industry known for both collective self-aggrandizement and individual self-loathing. You might say that AI companies are outsourcing the difficult and costly task of making contentious and disputed claims to the industry that is qualified, or at least willing, to do it, hopefully paying enough to keep the enterprises afloat. Or you might say that the AI industry is paying the news media to eat shit as it attempts to automate the more lucrative parts of its business that produce less animosity — that it’s trying to buy its way through a near future of inevitable, perpetual user outrage and politically perilous backlash and contracting with one of the potential sources of the backlash to do so. Who can blame them?

This isn’t unprecedented: You might describe the less formal relationship between the news media and search engines or social media, which rewarded the news media with monetizable traffic in exchange for “quality, real-time news content,” in broadly similar terms. Google and Facebook hastened the decline of print and digital advertising and disincentivized subscription models for publishers; at the same time, absent a better plan, the news media lent its most valuable content to the platforms (arguably at a cost, not a benefit, to their brands). But it’s also distinct from what happened last time: AI firms have different needs. Social media feels alive and dynamic because it’s full of other people whom the platforms are happy to let say what they want. Chatbots feel alive and dynamic because they’re able to infinitely generate content of their own.

The main question this would raise for media companies — and, hey, maybe it’s not about this at all! — is whether they’re being paid enough for the job. Functioning as newswires for what AI firms are hoping represents the future of the internet is arguably a pretty big task, and serving as a reputational sponge, or liability sink, for ruthless tech companies sounds like pretty thankless work.