The Unbearable Anthropocentrism of Our World in Data

How billionaire elites help fund an Oxford statistics lab that makes the destruction of Earth look just great. Roughly a decade ago, a 30-year-old economic statistician at Oxford University named Max Roser set out to transform the way we see the world using datasets. As he later described his mission in a statement of purpose,he wanted to instill “trust in ourselves” More

The post The Unbearable Anthropocentrism of Our World in Data appeared first on CounterPunch.org.

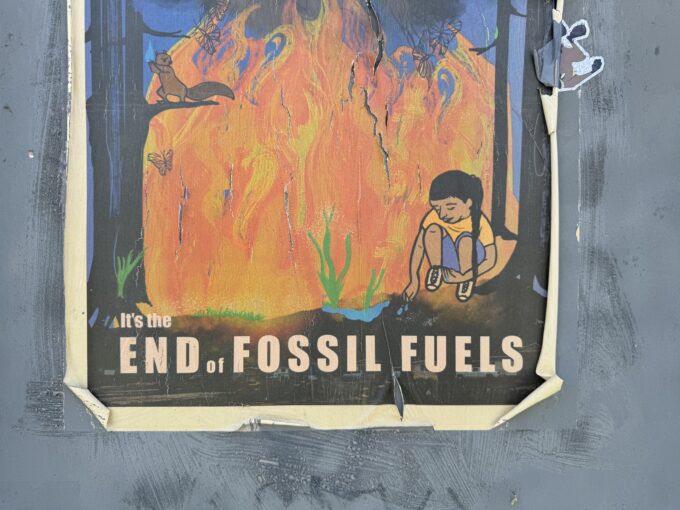

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

How billionaire elites help fund an Oxford statistics lab that makes the destruction of Earth look just great.

Roughly a decade ago, a 30-year-old economic statistician at Oxford University named Max Roser set out to transform the way we see the world using datasets. As he later described his mission in a statement of purpose,he wanted to instill “trust in ourselves” that we can “achieve extraordinary progress for entire societies.” His worldview rested on what he considered the three most salient facts of global civilization: “The world is awful. The world is much better. The world can be much better. All three statements are true at the same time.” The world, having improved greatly for Homo sapiens, can be continuously improved, Roser believed, so long as we do not lose faith in the drive and innovation of global capitalism.

In 2013, Roser founded a research initiative at Oxford to further this sunny agenda. He called it, to honor the scope of his ambition, Our World In Data (OWID). Over the past decade, OWID has become a go-to source for mainstream journalists looking to publicize numbers that purport to ballast the idea of the ever-improving human condition. A visit to the OWID homepage is an excursion into these chipper metrics of progress across every conceivable subject, from employment to poverty, health to literacy, and education to the environment.

One can learn, for example, that the share of people living in extreme poverty, has plummeted since the 1970s; that GDP per capita after 1945 skyrocketed in the U.S. and Western Europe, and has been rising – far more slowly, and only recently – in the rest of the world; that child mortality is way down; that the share of world population that’s undernourished is declining; that the literacy rate is way up; and that 90.44 percent of people on Earth now have access to enough electricity at least to charge a phone or power a radio four hours a day.

“It’s hard to imagine,” Roser writes in one of his many essays that celebrate the good news, “but child mortality in the very worst-off places today is much better than anywhere in the past.” He cites Niger as an example, the country with the highest mortality today, where about 14 percent of all children die – a rate three times lower than even the best-off places in the pre-industrial past. Still awful, but better than ever.

So it goes at Our World In Data, with hundreds of datasets pleasantly presented and easily clickable, serving deadline-addled journalists and a lay public accustomed to simple numbers. According to the analytics company Critical Mention, Roser has had great success with this model, with OWID’s work referenced in nearly 25,000 articles in 2022.

For obvious reasons, Roser’s cheerful view of capitalist business-as-usual – and the data that would seem to support it – has made him a darling of libertarian market fundamentalists, who have lavished praise on his work. His admirers include some of the most extreme right wing think tanks in the U.S. and U.K. Among these are the Cato Institute, spawn of the noxious fossil fuel magnates Charles and David Koch; the American Enterprise Institute, best known for its spreading of lies to foment the US-Iraq War in 2003; the Foundation for Economic Education, the oldest libertarian think tank in the U.S., founded by business interests to peddle pro-market, antigovernment ideology; and the Institute of Economic Affairs, a U.K.-based organization that has promoted climate-change denial.

Roser’s most important supporter, providing hundreds of thousands of dollars in funding, is the world’s fifth richest man, Bill Gates. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has been the single largest donor in recent years, funding “general operations and data infrastructure development” along with “core project activities.” Gates and Roser know each other personally. Gates has referred to OWID as his “favorite website.”

Other notable allies are the philosophers and social theorists who make up what’s called “effective altruism.” EA is a boutique ideology of wealthy elites who wish to do the “most good” in the world through charitable giving. Silicon Valley tech bros have been prominent devotees, including Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz and Estonian billionaire Jaan Taallin, developer of Skype.

According to the EA platform, pursuit of lucrative jobs within the profiteering framework is the ideal, as this provides more disposable income for donations to EA-approved charities. EA philosopher William MacAskill, who teaches at Oxford University, has advocated hiring on with “immoral organizations” if it increases income for ethical giving. Put another way: If maintaining an exploitative, unjust system means more profits for elites, then utility can be maximized, so long as elites practice some manner of “effective” and “altruistic” philanthropy. Philosopher Emile Torres, a one-time EA enthusiast and now postdoctoral researcher at Case Western Reserve University, says that the movement “ultimately reinforces the neoliberalism that is, in fact, a root cause of so many of our global problems.”

OWID is so closely tied with EA that it shares office space with the Centre for Effective Altruism, the movement’s flagship organization, which was founded in 2012 by MacAskill and Toby Ord, who also teaches philosophy at Oxford and, alongside MacAskill, is a leading public intellectual of the movement. The Centre for Effective Altruism is listed as an OWID donor, and Roser has cited Ord as a key reviewer of his work. One of EA’s biggest fans is Elon Musk, who is also a funder of OWID.

Given the support that Roser enjoys from billionaire oligarchs at the pinnacle of the capitalist system, one wonders if it is a coincidence that so much of the data he headlines for public consumption happens to valorize that system. The chief narrative that OWID deploys is that progress is due to economic growth driven by profit-seeking private enterprise and breakneck industrial productivity. He has made this view explicit in his essays published on OWID’s website. No mention that poverty mostly has been alleviated by the power of the state regulating capital, redistributing wealth, and providing services, counter to a system of immense inequities. Roser never mentions the labor, civil rights, and anti-colonialist movements that have pressed for social welfare benefits, safety nets, legal protections and political liberation for the poor. In his superficial telling, “The history of economic growth is the history of how societies leave widespread poverty behind by finding ways to produce more of the goods and services that people need.”

“Impoverished even as incomes rise”

While in the vast piles of data at OWID you will find no mention of political movements that have bettered the human condition by challenging the supremacy of capital, you will also find nothing that reveals the complex realities of what happens when societies outside the vaunted system of economic growth are absorbed into it and made to conform to its rules.

Consider the observations of University of Virginia anthropologist Peter Metcalf, who wrote in Al Jazeera in 2021how “simplistic stories of GDP growth blind us to the extraordinary social and ecological destruction that growth so often entails.” Metcalf spent decades studying an Indigenous community in the state of Sarawak, in the Malaysia-controlled part of the island of Borneo. He watched it transform from a place where the villagers had no money but lived well to one where GDP went up and they could “barely feed themselves.” They had been, in Metcalf’s assessment, “impoverished even as incomes rise.”

“I did my first fieldwork in Sarawak in the 1970s, in the longhouse culture,” Metcalf told me. “I did not know then that that world was about to be destroyed.”

The village where he studied consisted of roughly 350 people who lived under one roof, in a traditional longhouse typical of central Borneo at the time. He described life in the longhouse in a retrospective he wrote for Al Jazeera:

An open verandah ran along the side of the house facing the river, while the other side consisted of a row of family apartments. Their farms were some hours away by canoe, along small streams that led into the hills. During the season of cutting and planting, and again during the harvest, everyone was busy at the farms and the longhouse was empty. At other times, it was bustling and full of life. There was a powerful sense of shared history and tradition, including elaborate seasonal festivals and feasts. No one went hungry in the longhouse.

In the 1980s, these lifeways began to change, largely due to massive plunder of the landscape on which the dwellers of Sarawak depended, plunder which took the form, primarily, of the clearcutting of forests “at a rate unprecedented in human history,” according to Metcalf. Fueled by capital from West Malaysia, Hong Kong and Japan, timber barons “tore through the forests of Sarawak.”

“After they cut the rainforest down, they planted oil palm,” Metcalf told me. “You need a hell of a lot of manpower to cut the palm fruit. The men of Sarawak became part of that labor force. Now they lived in the cash economy. They were better off, yeah? In point of fact, their lives had become stunted.”

Metcalf drilled down to the heart of the matter in his piece in Al Jazeera. “The astonishing thing,” he wrote, “is that all this is smugly reported as development, as ‘growth,’ but this glossy narrative hides a much darker reality.” While the World Bank reported that poverty in Borneo had been reduced, “rising incomes don’t come anywhere close to compensating for the livelihoods that the longhouse people have lost,” observed Metcalf. “Nothing can compensate for the loss of food sovereignty and economic independence, and of course the loss of the rainforest.”

In the world that Roser depicts at OWID, however, no loss can be made visible, because the statistics – all that matters – show Malaysia tracking the gold standard for quantitative progress: GDP up, ergo poverty reduced, life better. Metcalf charges that “the whole narrative of poverty reduction is a charade.” The winners in Borneo, he says, have been “the corporations and elites who leech the labour of the new precariat” – people once free and independent in the longhouse culture but now servile, in the chains of capital, severed from their landbase.

Growthism’s tragic real-world consequences for the people of Sarawak – with the metric of per capita GDP revealed as hallucination – is no outlier but instead a commonality among the Indigenous of the global south. Ashish Kothari, co-founder of the environmental non-profit Kalpavriksh, in Pune, India, has spent decades looking at the real costs of his country’s rise to the status of economic powerhouse. He cites estimates that some 60 million people in India have been displaced since the 1950s to satisfy the needs of the growth machine. I told Kothari about Metcalf’s findings in Borneo. “This is exactly what has happened to community after community that has had to make way for ‘development,’” Kothari told me in an email. “Having been with and spoken to many such people, e.g. in the Narmada Valley where dams have displaced tens of thousands, I can attest to the deep emotional and psychological trauma, which no amount of cash compensation can make up for.” In Uttarakhand, Maharashtra, Odisha, and many other states, Kothari and his colleagues have gathered accounts of “declining natural forests and the biodiversity in them.” (The Indian government has been notoriously lax in tracking biodiversity loss, such that statistics are unreliable and partial; in the 2012 book Churning the Earth, Kothari and co-author Aseem Shrivastava concluded that up to 10 percent of India’s wild animal species were then threatened with extinction, and he believes the situation is worse now, “because ecological damage has only intensified, including in areas previously left ‘undeveloped.’”)

In Odisha, Kothari interviewed an elder of the Dongria Kondh Indigenous people who had fought successfully against proposed mining by the U.K. company Vedanta. “I have been to Bhubaneshwar city,” the elder told him. “I found that you cannot drink from your streams there, that women don’t feel safe walking around at night, that crossing a street is full of danger. Here in our forests, we are free to go where we want, we have fresh water and air, our women are not afraid … why would I want to give up this life and become ‘developed’ like you?”

The truth about the “age of destruction”

You will also not find headlined at OWID the data that a group of climatologists, ecologists, earth system analysts, and sociologists marshaled for the groundbreaking “Earth at Risk” report, published this April in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors identified three evils – imperialism, extractive capitalism, and overpopulation – propelling the “age of destruction” that has accelerated since the turn of the 21st century. They sounded once more the longstanding warnings that we are “past Earth’s material limits, destroying critical ecosystems, and triggering irreversible changes in biophysical systems that underpin [the] climatic stability which fostered human civilization.” They projected a “bleak outlook for global security” on a planet where more than a fifth of major ecosystems are at risk of “catastrophic breakdown” within a human lifetime. They suggested that “nature may impose its own population correction” – read: mass death – “before standard projections [of 10 billion-plus people by 2100] are realized.”

It’s widely agreed that one of the prime factors behind climate derangement, ecological impoverishment, and biodiversity crash is the growing number of people, in particular the world’s middle-class high-consumer population, which has been growing in leaps and bounds since the turn of the century. (The global middle class – wherein the impact-variables of “population,” “affluence,” and “technology” are fused into one single devastating blow on planet Earth – is headed upwards of 5 billion by 2030.)

Reports from the United Nations Population Division, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, and the Royal Society of the U.K. are unanimous in identifying population growth as a chief factor in humanity’s headlong plunge toward catastrophe. The UN Population Division reports that efforts to eradicate poverty, end hunger, and ensure universal access to essential services – health and education, for example – have “become increasingly difficult for countries experiencing rapid population growth.” According to the UN, of the 129 countries projected to experience an increase in drought exposure mainly due to climate change over the next few decades, 61 will do so largely because of skyrocketing human numbers. The IPCC states flatly that population growth, especially of the consumer class, is a key driver of greenhouse gas emissions. It is also one of the most wide-reaching agents of biodiversity loss. According to IPBES, the fact that natural ecosystems “are experiencing massive degradation at rates unprecedented in human history” is because too many people are now consuming too much from nature. The Royal Society reports that more people seeking ever-greater affluence means “ever more natural habitat is being used for agriculture, mining, industrial infrastructure and urban areas.” As biologist and filmmaker David Attenborough explained, “All our environmental problems become easier to solve with fewer people and harder – and ultimately impossible to solve – with ever more people.”

In Roser’s world, however, none of the data that shows overpopulation as a problem need be countenanced. Roser would have us believe, au contraire, that the concept is itself a “myth.” One of the informational videos on population growth that Roser helped produce, with funding from the Gates Foundation, features a narrator who, with reassuring cadence, tells us that fear about human numbers is based on “legend,” “apocalyptic prophecies,” and “unfounded panic.” The falsehoods pile high in a mere seven-minute video. Roser makes the claim that total fertility rate (TFR) drops solely through economic growth and industrial development. Decades of scholarshiphave shown that in fact TFR is most effectively reduced with family planning programs and girls’ and women’s empowerment. The video includes a galling misrepresentation of the heroic history of family planning, particularly as it cites plummeting fertility rate in two countries, Bangladesh and Iran, where TFR slowed not because of economic development – as claimed in the video – but because the governments in both countries made contraception and abortion widely available and, of greatest importance, funded publicity and educational campaigns that encouraged smaller families.

Roser tells us that population growth is “a promise,” because “more people is going to mean more people able to advance our species.” This is the old canard of cornucopianism, which holds that free markets coupled with population growth and technological innovation will lead to a world of cleaner environments and lifestyles of expanding abundance and heightened well-being. The concept is widely valorized by a public that wants to believe it – the “legend of overpopulation” video has almost 14 million YouTube views – and by media gatekeepers who zealously spread the word. Consider that the Washington Post, in the fall of 2022 on the occasion of Homo sapiens surpassing eight billion in number, deployed language that was distilled cornucopianism. “The World’s Population is 8 Billion and Rising,” said the Post. “That’s probably a good thing.” The teeming billions amounted to a grand resource, the Post contended, because out of the mass would emerge the innovative capitalist geniuses who can solve climate change and all our other myriad crises.

As Harvard historian of science Naomi Oreskes has shown, cornucopianism – which takes its name from the cornucopia, the horn of plenty of Greek mythology – is itself a myth. “The argument goes that the greatest resource on Earth is human creativity, intelligence and ingenuity,” Oreskes told me. “So we should encourage people to be fruitful and multiply. But too many people can be too much of a good thing, as when they take over the whole planet, when they drive out other forms of life, when they drive climate change. Really, it’s an absolutely infuriating argument because it’s so wrong on so many obvious levels.” Writing in Scientific American in response to the Post’s editorial, Oreskes suggested that the smarter path would be to curb population through concerted and well-funded family planning. “We ought to have a plan for slowing the destructive surge in human population. But we don’t,” she wrote. Instead, we are “fatuously assuring listeners that in the future, somehow, all will be well.”

Graphs to flatter the global elite

Since its inception in the 1970s and subsequent mainstreaming in neoliberal discourse, cornucopianism has seen many virtuoso adherents, almost all of them economists, offer up deluded nonsense. Julian Simon, late of the Cato Institute, opined in 1992 that humanity now has “in our hands…the technology to feed, clothe, and supply energy to an ever-growing population for the next seven billion years.” On another flight of fancy, Simon averred that “in the end, copper and oil come out of our minds.” When he was chief economist of the World Bank, Harvard’s Larry Summers, who would later serve as secretary of commerce under Barack Obama, was laughably wrong when he promised there are “no limits to the carrying capacity of the earth that are likely to bind any time in the foreseeable future. There isn’t a risk of apocalypse due to global warming or anything else.” The limits of the carbon sink are now revealed in its saturation, as humanity breaches six of nine planetary boundaries, and as scientists warn over and over that, yes, we are headed for a bind of epic proportions that might resemble apocalypse.

Recent infamous additions to the cornucopian school – Bjorn Lomborg, Steven Pinker, Michael Shellenberger – have proved themselves no less adept at making observations divorced from Earth science, biophysical reality, and common sense. A reviewer for the London School of Economics, hardly a bastion of radical climate action, found Lomborg’s blithe claims about “climate change panic” to be “based on fantastical numbers that have little or no credibility.” When Peter Gleick, a MacArthur Fellow and expert on climate and water systems, reviewedShellenberger’s cornucopian manifesto, Apocalypse Never, he found it a welter of “logical fallacies [and] arguments based on emotion and ideology…and the selective cherry-picking and misuse of facts.”

The newest kid on this block is the senior researcher at OWID, Hannah Ritchie, a 30-year-old data scientist, who boasts a PhD from the University of Edinburgh. Her first book, Not the End of the World, published in January, is classic cornucopianist conversion literature, Ritchie the bright-eyed proselyte who once prophesied climate doom but now wants to lead us to the promised land alongside Lomborg and Shellenberger. “I’m convinced that if we’re to make progress on climate,” she writes, “we need to lift [the] cloak of pessimism.” The way to do that is look for “the signs that things are getting better.” Hers is the stuff of fatuous assurance. She has pronounced coal on its way out, renewables on their way up, the Eden of green capitalism on the horizon. “Things are moving fast – and at an increasing pace,” she tells us.

Reviewers of her work have not been kind. Shane White, the founder and director of the educational nonprofit World Energy Data in Australia, called Ritchie’s book “hopium.” Though there have been admirable advances in renewables, consider the data that Ritchie opted not to share with her readers. In 2023, the world saw record coal production, record primary energy produced from coal, record electricity generation from coal, record oil and gas production, and, overall, fossil-fueled electricity generation double that of renewables. According to World Energy Data, fossil fuels were subsidized at a rate of $13 million per minute in 2022, totaling $7 trillion. “So gasoline cars are on their way out, maybe coal too, and the energy transition is changing the game?” White wrote me in an email. “Nothing like another fix of hopium.” (“Drugs,” he quipped, “have always been a severe problem in Scotland.”) Ecosocialist writer Andrew Ahern, analyzing Ritchie’s work for a lengthy review in Sublation Magazine, concluded that she had found a pleasant niche “making graphs to flatter the global elite.” As Ahern put it to me, “Ritchie is a young, cheery and intelligent person that the capitalist class can prop up to try and propagandize young people.”

The blinders of human supremacism

The authors of the Earth at Risk report, seeing that humanity faces terrible trouble, advocated a radical change of our political economy. They envisioned “a critical paradigm shift…that replaces exploitative, wealth-oriented capitalism with an economic model that prioritizes sustainability, resilience, and justice.” One of the authors of the report, Eileen Crist, a professor emerita of the Department of Science, Technology, and Society at Virginia Tech, has written about what she says is the driving ideological force in our age of destruction: human supremacism.

Crist would have us ask whether human supremacism constitutes the most ignorant prejudice of all, as it operates under the demonstrably false belief that the only measure of progress is that of Homo sapiens’ well-being. Subordinate to human ends, the living planet is reduced to a resource for the aggrandizement of the one chosen species.

At OWID, the fate of other-than-human life on Earth is never centered in the information it offers to the public. There are no headlines on how the growth regime is crushing wildlands, killing out wildlife, and overwhelming the planet with pollutants.

Yet, behold: this is our world, in data. Ninety-nine percent of the tallgrass prairie in North America, once the largest such ecosystem on Earth, has been wiped out. Amphibian, songbird, and mollusk populations are collapsing. Since 1970, industrial civilization has precipitated a “devastating” 69 percent decline in the total number of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish worldwide. There’s no room for the wild things when humans, cows, chickens, pigs, dogs and cats crowd out everything else, so that 96 percent of mammalian biomass now consists of Homo sapiens and our domesticated animals. The oceans are dying. An estimated ninety percent of large fish are gone, coral reefs are bleaching, and six times more plastic floats in saltwater than phytoplankton. Insects are disappearing – declining at an “unprecedented rate of 2 percent per year” – and the skies rain microplastics. GDP per capita may be up, and some of us are doing better than ever, but the world as a biotic whole is poorer. Overarching all this is the saturation of the carbon sink with thermal pollutants that threaten literally to burn down and kill whole communities, animal and human, if the pollution continues – which clearly is the trend, with each year recording a steady rise of fossil fuel exploration and greenhouse gas emissions.

Roser and Ritchie would have us revel in the graphs that measure the length and breadth of human supremacism. “Happy Hannah,” as one critic describes her, has no interest in the datasets showing the non-human worlds that have already ended under the system she defends. It appears to be lost on these people that in the late hour of faltering modernity, when human dominance is leading to ecological havoc and climatic upheaval, the time has come to cease the exaltation and imbibe a dose of humility.

They are incentivized otherwise, of course. Bill Gates has fêted Ritchie at his blog, declaring her book “essential and hopeful,” claiming it promises a world in which “trade-offs between human well-being and environmental protection…no longer have to be made.” In his review of Not the End of the World, Gates parroted word-for-word Max Roser’s language of hearty optimism. “The world is bad,” he wrote, “but much better.”

Ritchie returned the favor in an interview Gates granted her, in which she made sure to lob him softball questions. That Ritchie so readily would bend her knee before one of the most powerful capitalists on Earth tells us all we need to know about her politics, careerism and talent for placation. They’ve got a good thing going at Our World in Data, and no need to blow it by messing with their paymaster.

The post The Unbearable Anthropocentrism of Our World in Data appeared first on CounterPunch.org.