How the 49ers Built—and Sustain—the NFL’s Best Personnel Development System

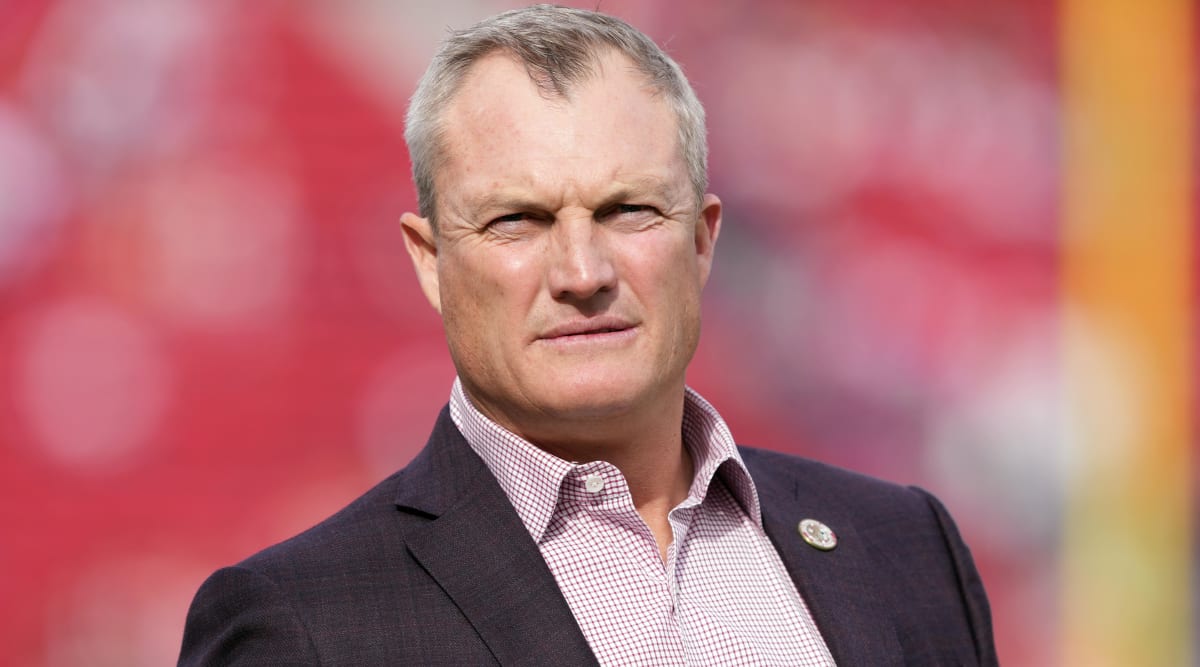

Year after year, the organization built by coach Kyle Shanahan and GM John Lynch is pillaged by rivals aiming to replicate their success. And yet, it doesn’t skip a beat.

Kwesi Adofo-Mensah remembers the tense moments before draft meetings. He was the analytics guy about to go into those conference rooms with coaches and scouts, with beliefs hardened by years on the field and the road. He knew his reports would be picked apart. He knew his data might come under tighter scrutiny than anyone’s.

“I would be almost sick before the meetings because I knew I had to go stand in front of a room, I knew I would be challenged,” says Adofo-Mensah, then 49ers director of football research, now the Vikings GM. “But ultimately, that made me better. It sucked at the time. You wish everybody would just say, I agree with you. They would challenge you. I remember one time [Robert] Saleh and Bobby Slowik—again, talk about all the people I got to work with, Saleh and Bobby Slowik—asked me something about one of the things we do with pass rushers and they said, Give me a list of these guys with these parameters.

“They almost want to do the analysis themselves to confirm it. I always appreciated it. They trusted me enough to ask that second question. Now, that's their knowledge. And now, it's our knowledge.”

This is Year 7 for Kyle Shanahan and John Lynch in San Francisco.

They’ve been to four NFC title games, two Super Bowls and will try to win their first Lombardi Trophy on Sunday against the Kansas City Chiefs. They’ve built this team from the ground up, taking over a broken football operation and building back to the Niners’ old standard, in Lynch’s words, brick by brick. There are a lot of reasons for that—Shanahan’s coaching brilliance, the job Lynch’s staff has done picking players and the job the players have done among them.

Stan Szeto/USA TODAY Sports

But there’s one overarching thing that can tie all of it together. The Niners have been elite at developing people. It’s not just players. It’s people, in general. Scouts. Coaches. Analytics folks. And as a result, in a league full of owners lusting after the idea of manufacturing a setup to make their franchises the Apple of pro football, the Niners have organically become just that—a forward-thinking, efficient, and self-sustaining operation.

They can lose Adofo-Mensah, Martin Mayhew, Ran Carthon and now Adam Peters on the personnel side to GM jobs, and Saleh, Mike McDaniel, DeMeco Ryans, Mike LaFleur and soon Klint Kubiak to coaching promotions, and not just survive, but maintain the standard that’s been set over the past decade. And it’s because of stories like Adofo-Mensah’s.

It’s an environment that’s identified, educated, and pushed young people, and kept churning them out so when those young people leave, more are there to replace them.

It’s why the Niners are here again, four years after taking about as crushing a loss as is imaginable in football. It’s also why, even with some aging players and a looming cap crunch, it’d be silly to think they won’t be back again soon.

The vision for all this, for John Lynch, came by osmosis.

As a player in Tampa, under Tony Dungy and then Jon Gruden, his Buccaneers achieved similar “model rebuild” status—and had their coaching and scouting staffs picked away at relentlessly. So it was that in early 2001, as Herm Edwards was leaving for the Jets, and Lynch was at the Pro Bowl in Hawaii, his hotel phone rang. It was the team, and Lynch was just a little nervous that they were calling to cut him.

“It was before cell phones. The old light was going off,” Lynch says. “It's Tony, Monte [Kiffin] and Rich McKay. I was like, You guys really going to cut me? … We got good news and bad news. What do you want first? I asked for the good news. We finally found a replacement for Herm. We’d interviewed 24 people. I said OK, that's great news. Who is it? … It's a guy named Mike Tomlin. OK, what's the bad news? You're two years older than him.”

Lynch smiled, and kept going, “That staff was ridiculous. I've always been real conscious, my dad was a business executive, you’ve got to put a great team around you. I've always been cognizant, I've seen it. It's so important.”

That, of course, is what the Niners set out to do in 2017. Adofo-Mensah was retained from the Trent Baalke regime. Owner Jed York suggested that Lynch, as a first time football exec, find someone who’d been a GM before—Lynch agreed and brought in his old Buccaneer teammate, and ex-Lions GM, Mayhew. Peters was a sharp young mind in the Denver draft room that Lynch connected with when John Elway invited him to sit in with the Broncos.

[Super Bowl 2024: Latest news and analysis | How to watch]

On the coaching side, things came together similarly, with a focus on, first and foremost, finding good people—and just as important, people who fit together.

“There's a big buzz word in sports and life and organizations—they're connected,” says Lynch. “We're a very connected group. I do believe things start at the top. We're connected with our ownership. Kyle and I are connected. Kyle's tough. He's demanding. I have my own issues. The other thing I hope they all say is we balance each other out. He can be very hard. I tend to be uplifting. I think that balances an organization out. We're very connected.”

And that connectivity was prioritized on the ground floor in the construction of Shanahan’s staff, with McDaniel, Saleh and LaFleur among those who’d previously worked with him, and each of them enduring a vetting process that ensured the puzzle pieces would come together the way they’d envisioned.

Related: Super Bowl LVIII Newsletter: Dissecting the Brock Purdy System QB Debate

Along those lines, in January 2017, with Shanahan’s Falcons still in the playoffs and Lynch having just come to terms with York, the coach asked the GM to meet with Saleh, a young linebackers coach with the Jaguars who was part of a staff that’d just been let go. Despite the optics of that, Shanahan told Lynch he thought Saleh was the guy to run his defense—but wanted to get his GM-to-be’s feel before formally offering the job.

Lynch invited Saleh to San Diego to meet, and his wife Linda went to Staples to buy a greaseboard for the interview. It was set up outside behind Lynch’s house, and the two spent two hours talking football and getting to know each other.

“We basically interviewed him right there—Let's talk ball, Robert,” Lynch recalled.

Lynch could feel Saleh’s presence as he spoke, and how he’d fit into the larger picture. He was hired, effectively signing up for an education, as well as a job.

As Saleh, now coming out of his third year as the Jets’ coach, sees it, Shanahan and Lynch didn’t involve their lieutenants in everything, but they were willing to show them almost anything.

“With John and Kyle, not that every conversation is open to everyone, but there's a lot of discussion where you're a part of understanding the global thinking of roster construction, scheme, all of it,” Saleh says. “From a transparency standpoint, those two aren't insecure in the sense of, Hey, we've just got to have these private conversations. They're very open.”

And as a result, the coaches are always learning, and not just on their own sides of the ball.

It starts with Shanahan’s team meetings—through which players and coaches get to see how the head coach sees every aspect of the next week’s game, from what’s needed on offense, defense and special teams, to specifics on what needs to happen to beat the opponent at hand.

“His team meetings are gold,” Lynch says. “We spend probably more time in team meetings because Kyle's at his best when he's got a clicker in his hand. The defensive players start to understand offensive football. I always thought that helped me as a [defensive] player. I played quarterback growing up all the way to my junior year of college. I had an idea of how offenses were trying to attack. I played quarterback in a West Coast system for Denny Green at Stanford for my first two years. That always helped me. Our whole team gets that.”

"Far and away, the most impressive thing Kyle does is prepare the whole team for the game,” Kubiak added. “He talks to the whole team—offense, defense, special teams. He talks the defense's language, and he doesn't just stop at the offensive side of the ball. He is heavily involved in the defense and special teams. On game day, he's involved in all facets.”

It shows the players how to play.

It also gives the coaches a broader perspective on their jobs and the scouts insight into how their coaches think, and, in time, makes an impact on everyone.

Kyle Terada/USA TODAY Sports

One example—the offensive and defensive coaches started to become more in-tune to each other’s needs because their head coach has given both sides an overall roadmap that charts the path in how one phase of the game impacts the next.

“The communication between me and the two Mikes, LaFleur and McDaniel, and scripting— it was McDaniel saying, ‘Hey, need this front and this coverage. Can you give it to me here?’ ‘Yeah, as long as you guys give me these three runs. I need them today,’ ” explained Saleh. “ ‘Hey LaFleur, can you attack our corners?’ ‘Alright, I got you.’ It's just a constant collaboration of what you're trying to accomplish.”

That, in turn, flows down to the position coaches, who are learning from the coordinators, and even quality-control coaches, who are learning from the position coaches. And it allows for someone like Slowik, who started as a quality control coach for Saleh on his defensive staff, to evolve into a bright offensive young offensive coach, one that’d eventually go with Ryans to Houston as a coordinator.

“There's always that stigma of an offensive head coach or a defensive head coach, and that's all they focus their attention on,” says tight ends coach Brian Fleury, another riser on the staff now in his fifth year with the Niners. “Kyle's really broken through in a way to truly coach the entire football team and have the team take on his vision of what it should be. It really is incredible. I know Bill [Belichick] was very similar. He coached the whole team in New England. I think across the league, it's a little bit more rare. …

"There's definitely a lot of transparency within the building, too. Even across the lines from personnel to coaching, the communication is awesome. I think that the transparency definitely helps. You can help prepare yourself for what that next role is.”

Fleury then said there are examples of a position coach bringing in a quality control coach to present in his room, or coordinators letting position coaches do the same. And, as a result, the idea of moving a guy up the ladder isn’t so daunting, either for the team or the coach.

Lynch had plenty to learn when he landed in San Francisco in 2017, as both a GM and an NFL front office first-timer, but he did know one thing—the connectivity that he and Shanahan resolved to seek would have to come on a two-way street.

And so one place he started to pave that road came simply through listening to the people around him, and realizing how his scouts on the road could somehow feel like independent contractors, separated by more than just space from what the team was doing. That would be addressed, and in an intentional way.

“I had to learn, every couple weeks, to write something to them,” Lynch says. “Say you appreciate [their work]. Here's what's going on on our team. This guy's struggling. This guy's doing great. These are the guys they pour their heart and soul into, going out and identifying them. To feel them connected—I was never a road scout, I had to learn the hard way. You try to do things like that.”

Related: Super Bowl LVIII Newsletter: Kyle Shanahan’s Brilliance Is in the Details

Then, when those guys came off the road, as was the case with the coaches and players and Shanahan, they all got to see the way things were done, and feel the difference they could make. That was with Lynch, and it was also with Shanahan who, in the spring, would make himself accessible to the personnel people, so they could share his vision for the team.

"I know for me, it made the job easy,” says Carthon, now the Titans’ GM. “You know exactly what Kyle is looking for. You know exactly what it takes to play in Kyle's system, first and foremost. Then, over time, you spend so much time together, you start to learn outside of the position specifics. You start to learn the style of player that Kyle wants. … You know exactly what he’s looking for.”

Of course, there was training along the way.

In 2017, Shanahan and his coaches presented for the personnel people the granular details of what they wanted in every position, from the obvious (size, speed) to the harder-to-ascertain (personality, makeup). Ex-Niners exec Ethan Waugh, now the Jaguars’ assistant GM, would then supplement that with a program for scouting assistants—“I’ll forever say he’s one of the best I’ve ever seen at doing that,” says Carthon—to get them up to speed.

But most of what the personnel people got coming up through the ranks was experience, more than it was just learned.

“It was just a development environment,” says Adofo-Mensah. “There are some organizations, like Green Bay, where it's like scout school and it's this formal thing. This was never formal. That building is not formal. But it happens in an amazing way. You leave a team meeting with Kyle and he would say something that I wouldn't understand, and then I would go ask Martin, Hey Martin, he said this, can you explain it to me? Then Martin would get on my whiteboard and explain it to me, Ran would come into my office.

“That type of organic stuff happens all the time. It was an environment where people just wanted to learn from each other. There were enough connectors.”

Darren Yamashita/USA TODAY Sports

And on that side of the building, the two biggest ones are Lynch and EVP of football operations Paraag Marathe, who can stake a claim to being the NFL’s original analytics director, carries more than two decades of experience in the organization and is seen as being as smart as anyone in the sport. He’s also now settled into a strong role in the organization, after different previous regimes would utilize him in different ways.

Both are available to those who work for them, and Marathe can push personnel folks—and not just the guys like Adofo-Mensah, lead negotiator Brian Hampton and ex-team analyst Demetrius Washington (who wound up with Adofo-Mensah on the Vikings) who came up on the analytics side—the same way Shanahan does his coaches.

“You talk about a challenge?” Adofo-Mensah says. “You better bring your best s--t to Paraag's office. Because in 10 minutes, he’ll have never even seen what you've written, and he's asked you six questions that you maybe haven't thought of. He's just that quick.”

As for Lynch, Carthon quickly pointed to how Warren Sapp, Ronde Barber and Derrick Brooks, Lynch’s fellow Buccaneer Hall of Famers, spoke about him—“the ultimate leader, through and through”—as evidence of what York got when he listened to Shanahan, and gambled on a former player who would be coming over from TV.

In so many ways, that leadership would tie together the groups that guys like Peters and Marathe and, of course, Shanahan captained, and make sure the connection stayed strong.

Carthon sent over a picture from last March’s owners meeting in Arizona, with Lynch, Carthon, Adofo-Mensah and Mayhew sitting in a row in white folding chairs, and McDaniel, Ryans, Shanahan and Saleh standing behind them. It was, all at once, a sign of how the rest of the league wanted a piece of what they’d built—all eight were there for the 0–9 start in 2017, and the Super Bowl after the 2019 season—and also the balance of the pipeline.

Four coaches. Four GMs.

And so as Lynch and I sat in a quiet corner of the Niners’ team hotel Wednesday afternoon, I thought to hand him my phone and show him the picture his old pro scouting director had sent a few days earlier.

“A lot of pride,” Lynch says, looking at the picture. “These are all friends. We all remain close to this day. Some of them you even have to compete against, so that's not always fun. You take a lot of pride. We all came together. The first year was very hard. We lost five games by three points or less. It was an NFL record at the time. We were 0–9 at one point, but we kept it going. We found a way and we still haven't gotten to the ultimate goal. …”

He stopped, then continued, “These guys are special in their own right. Hopefully, we helped make them a little better. Kyle's really good. You're going to learn, if you're around Kyle. He's demanding. He has expectations, but he's a good person and they know that. … Football is tough, it's hard. You need people that love it and are willing to grind. They're all good people. We don't like working with people that aren't great people. These guys are all great people.”

Over the phone, I raised the picture to Adofo-Mensah, too—he didn’t even need much describing from me to know what I was talking about, nor did it take long to jog another memory for him.

Adofo-Mensah left the 49ers for the Browns in 2020. In his office in Cleveland, he kept a picture from the Cleveland draft in the early 1990s, with Bill Belichick running the show and guys like Nick Saban, Eric Mangini, Jim Schwartz and Mike Lombardi donning Coke bottle glasses and heavy sweaters that dated the snapshot and also marked how rare the opportunity to have groups like that one assembled.

“I used to just sit there and be like, I wonder if I'll ever be in an environment like that—not knowing that I actually was,” Adofo-Mensah says. “I look back, and I’d put our room up against anybody. There is this pride in all that you learn and what you helped build. It’s just gratitude. I don't think anybody who left there doesn't understand the good fortune they had to cross paths with all those people. I know my life's different because of it.

“I'll definitely be rooting for those guys on Sunday.”

So too will Carthon, and Saleh, and so many others that had a hand in building perhaps the NFL’s best roster, and maybe its most forward-thinking operation. Others, like Kubiak, will follow the path of those guys, in walking out the door after the game for new opportunities.

But what the 49ers gave them—and, just important, what they gave back—will be around long after they’re gone.