The Problem With Darling 58

The fight to save America’s iconic tree has become a civil war.

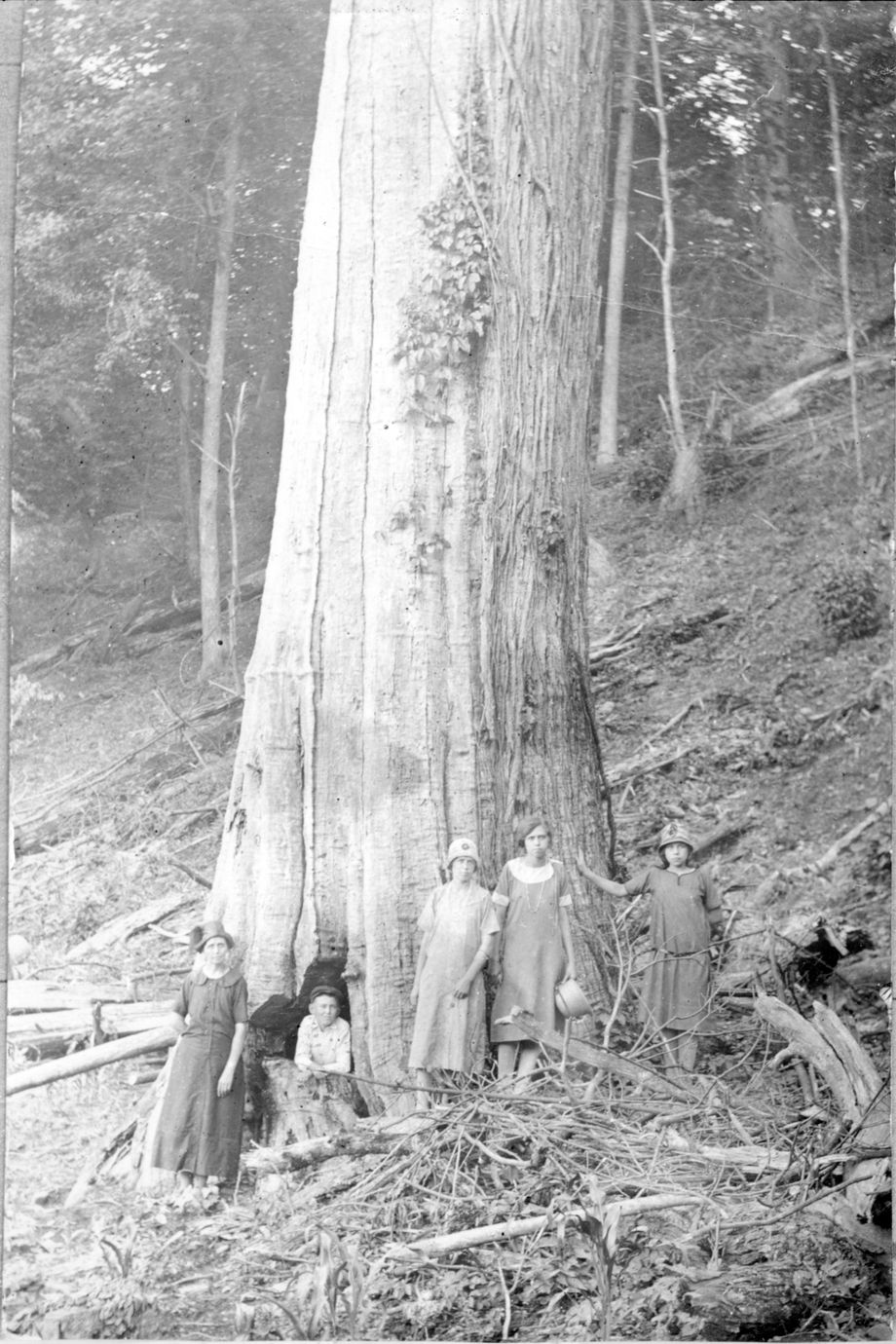

For the past two decades, Sara Fern Fitzsimmons has raised seedlings of the American chestnut in research orchards along the Eastern Seaboard, keeping them fed and hydrated and charting their growth. At the turn of the 20th century, the “redwoods of the East” dominated forests with their towering trunks, accounting for an estimated one in every four trees from southern Maine to northern Florida. They fueled a major timber industry, and their nuts were a vital source of food for both livestock and countless families. As one historian wrote, the tree “was possibly the single most important natural resource of the Appalachians.”

Last fall, Fitzsimmons noticed some of the baby trees seemed small for their age, with weak roots and curling leaves. Worse, they were getting sick as a cankerous orange fungus ate its way out of their trunks, suffering with a disease that decimated the species and to which the trees had been genetically modified to resist.

More than a few saplings died. So did the hope of rescuing the American chestnut tree from the point of near extinction, at least for now. A breakthrough in genetic engineering was intended to bring them back and transform the science of species restoration while potentially netting its inventors millions of dollars and wide acclaim. Instead, a mix-up in the lab has sparked a veritable civil war in the niche conservation community.

For the chestnut evangelists who’ve devoted years to restoration efforts, the fight to save the tree has always been personal. Now this fight is, too, amid accusations that the scientists who invented the GMO tree covered up the mistake as they sought federal approval and pursued potentially lucrative deals to sell their creation.

Tree world, says Andy Newhouse, director of the lab that invented the promised savior of the chestnut tree, “is definitely a little, little bubble. And inside that bubble, there’s a lot going on.”

In 1904, Herman W. Merkel, a forester at the Bronx Zoo, noticed chestnuts near the park’s perimeter were speckled with a strange orange fungus. Merkel called in William A. Murrill, a mycologist at the New York Botanical Garden, and the two men spent the next year identifying a fungus now known as Cryphonectria parasitica, imported on ornamental Asian chestnut trees. The blight enters via small wounds in the bark made by weather or insects and eats its way through before the trunk erupts open with a warty canker full of “yellowish-brown fruiting pustules,” which release spores to infect nearby trees, wrote Murrill. “No treatment can be suggested except the rigorous use of the pruning knife,” he determined. “The disease seems destined to run its course, as epidemics usually do.”

The blight ran through forests like a line of fire, killing close to 4 billion trees by 1940, and it still hasn’t burned out: When the viable chestnut roots below ground send up new shoots, they only live a decade or so before the fungus kills them, too. A small, determined cohort of scientists, growers, and tree lovers refused to accept the end of the chestnut epoch, and in the 1980s, two parallel rescue efforts began.

At a research farm in southwestern Virginia, growers working with the nascent American Chestnut Foundation began a breeding program, hypothesizing that crossing American chestnuts with their Chinese cousins would confer the latter’s resistance to Cryphonectria parasitica. Infected Chinese chestnuts, having evolved alongside the blight, simply wall it off and keep on growing. Subsequent “back-crossing” of the resulting hybrids over multiple generations aimed to create blight-tolerant trees that had all the characteristics of the American original.

Around the same time, an engineer named Herb F. Darling Jr. found some surviving wild chestnuts on his family’s land in western New York’s Zoar Valley. He thought they might provide the basis for a much quicker solution: transgenics — inserting one organism’s DNA into another — to create a genetically modified tree. When he approached the foundation for support, it turned him away: Its official position was staunchly anti-GMO. It’s an opinion much of the conservation community has long shared. The introduction of farm GMOs like Monsanto’s “Roundup-ready” crops has increased agricultural production, but it has also created new threats to biodiversity and drastically increased usage of the trademark herbicide.

Since their inception, those commercial GMOs have been deployed with an eye toward containment. Darling was proposing using the technology much differently. “For conservation, you want it to spread,” says Will Pitt, the foundation’s current president and CEO; that only alarmed foundation leadership further.

So instead, Darling started his own organization and partnered with Bill Powell and Chuck Maynard, geneticists at the College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF) at the State University of New York. Powell went on to identify an enzyme in wheat plants — oxalate oxidase, or OxO — that protects them from oxalic acid, the same compound Cryphonectria parasitica produces to kill chestnuts. He would spend the next several years inserting an OxO-producing wheat gene into different places along the chestnut genome, creating iteration after iteration of what he dubbed the “Darling” line after Herb, his benefactor. In 2012, he landed on a version that seemed to convey total blight resistance without changing the American character of the trees. He dubbed the revelatory version Darling 58.

After Powell and Maynard officially published their findings in 2013, there was “a big shift” in the chestnut community, says Newhouse, who began working on Darling 58 at ESF. Supporters clamored to know when they could get seeds to plant. The foundation’s hybridization plan had produced only marginal success, and it found blight resistance more genetically complicated than expected. It announced its full support for the transgenic program and ESF, and threw its weight behind applications asking the federal government to deregulate Darling 58, allowing it to be planted, basically, anywhere and by anyone. The foundation became ESF’s primary scientific partner and financial backer, funneling the lab annual donations in the six figures.

With Darling 58’s blight-resistance properties proven in the lab, and seedlings planted at carefully monitored test sites, it was just a matter of getting the government to deregulate Powell’s creation. That would make it the first GMO designed for conservation and approved for release into wild ecosystems. The move would open a fresh chapter of species-restoration science and pave the way for transgenic solutions for all manner of endangered plants and animals. “They’re all kind of lined up behind this,” says Pitt.

In 2022, Powell was diagnosed with colon cancer and given a two-year prognosis. At the same time, he and Newhouse, his longtime protégé, began meeting with American Castanea, a newly formed company whose founders saw a huge opportunity in meeting the intense demand for seedlings they expected to follow deregulation. American Castanea would agree to pay ESF for distribution rights to sell millions of transgenic seedlings worth millions of dollars.

The foundation, however, balked at the potential involvement of a for-profit company after repeated insistence from Powell that rights to Darling 58 would remain in the public domain. Internally, the leadership referred to Powell’s deal with American Castanea as “the betrayal.” They met with SUNY leadership, threatening to dissolve the partnership if the deal was made official. Soon after, Newhouse says, he was “uninvited” from the foundation’s annual meeting. “That was definitely a big red flag.”

Meanwhile, the foundation’s scientists were growing concerned at Darling 58 test sites. Many of the trees seemed stunted and unhealthy. Their leaves were browning and folding in on themselves, and a surprising number were dying, succumbing to the fungal blight they should have been able to resist.

The scientists at the foundation raised their concerns with Newhouse and ESF and pushed for the lab’s newest research about the performance of Darling 58. What information they received felt incomplete, and some began to wonder if ESF was hiding something. “We have weekly science calls they’ve been on since 2019,” says Sarah Fern Fitzsimmons, the foundation’s chief conservation officer. “There’s a history of not being transparent with data. I look back through the reports they compiled for us for the grants we gave them, and everything’s awesome: It’s cherry-picking the good and not letting on that anything was amiss at all.”

Last spring, while foundation scientists in the field were wondering what could be wrong with the trees, Thomas Klak, an environmental-science professor at the University of New England in Portland, Maine, was struggling to produce Darling 58 plants with two copies of the OxO gene. He reached out to Ek Han Tan, a geneticist at the University of Maine who developed a test to analyze their genome.

“The line that Tom has been using — that everyone has been using — was supposedly derived from Darling 58, and there was a good genetic map of the transgene on chromosome seven,” Tan says. But when he couldn’t find that gene on any of Klak’s samples, he started to wonder if they all might have the wrong tree.

Eventually, Tan found the trees’ OxO gene on chromosome four — the insertion point for an earlier transgenic iteration called Darling 54. For the past decade, the many scientists trying to save the chestnut had been working with the wrong tree. Functionally, Darling 58, the tree touted as the great hope of the chestnut and the next frontier in species restoration, did not exist.

In October 2023, Klak and Tan broke the news to Newhouse and his ESF colleagues. Newhouse says ESF began working to confirm, as initial tests weren’t “entirely consistent” with the hypothesis that the trees were Darling 54. Nearly a month later, after following up repeatedly with the ESF team, Tan looped in the foundation’s science director. It was the first the foundation had heard of the major mix-up.

Fitzsimmons says ESF chalked it up to mistaken identity when the first generation of transgenic clone trees were made. “You think you’re getting pollen from a Darling 58 tree, but you actually got it from Darling 54,” she says. “So, you take that pollen and put it on chestnuts in the field and you assume everything subsequently will be 58. But everything derived from that initial pollination.”

Six days after Tan alerted the foundation, on November 12, Powell died. He never knew that he’d spent years planting the wrong tree, Newhouse says. By this point, the partnership he’d forged between ESF and the foundation was collapsing over his creation.

ESF, though, was undeterred by the startling discovery about Darling 58 and announced a $636,000 grant from the USDA to support studies of the “performance of Darling 58 chestnut trees as they start to mature in real-world conditions,” but made no announcement about Klak and Tan’s discovery. It forged ahead with getting approval from the FDA and EPA as well. On December 8, the foundation decided to blow the whistle. It issued a press release calling the Darling trees “unsuitable as the basis for species restoration,” withdrawing support for deregulation, and declining to further fund the line’s development. The potential deal with American Castanea was dead.

“To this day, we’ve never heard anything directly from ESF,” says Pitt, the American Chestnut Foundation’s president. If Tan and Klak hadn’t shared their findings, Pitt wonders if ESF ever would have “told us, told the public, told anyone.” “As a nonprofit organization, we can’t hide things from our members or the public. If we wouldn’t have brought this out, we would be complicit with a cover-up.”

Pitt estimates the foundation has funneled close to $3 million to ESF over the last decade. Given that, the pending deregulation applications, the USDA grant, and rumors of an additional million dollars promised to ESF upon deregulation from another donor, he says there were “more than a million reasons” for ESF to sweep the error under the rug. “The stakes are extremely high: If this was successful, ESF would be world-renowned.”

It’s necessary to demonstrate success, Newhouse concedes, “in order to keep doing the research. But you don’t want to overstate, and that’s the tightrope.” He maintains that any delay was because ESF was doing its own testing on the trees. “It wasn’t that we sat on things or tried to cover them up,” he says. “We wanted to be sure of what we had and not share speculative information.”

But Pitt recalls a conversation in the fall — before the Darling revelation — where Newhouse and other ESF leadership were discussing plans to establish a major research institute. “I said, maybe the problem is we have two different goals,” Pitt recounts. “If you’re successful, you’re going to build a bigger forestry institute. If I’m successful, I’m going to be out of a job. That’s what success looks like to me; that I’m no longer needed. That is a very different way of looking at the world.”

Newhouse has repeatedly said the mix-up is little more than a naming error. While Darling 54 doesn’t appear to offer the same blight resistance Darling 58 promised, it might still be able to tolerate the fungus a bit longer than an entirely wild American tree. Though Newhouse concedes it’s not the tree that’ll rescue the species, it’s still “promising,” he says, and ESF is forging ahead with deregulation efforts. He has provided updated data to the USDA and said he doesn’t think the applications should be drastically affected. “The series of environmental tests we’ve done were actually done with Darling 54; some knowingly, and some when we thought it was 58,” he said. “We’ve seen that it’s not detrimental, it’s not harmful to other organisms.”

Fitzsimmons is not so sure. In addition to evidence of lower-than-expected blight resistance, Darling 54’s chromosome tweak causes the deletion of more than 1,000 DNA base pairs, the ultimate effect of which is hard to know. “It’s not something you want to deploy into a restoration population,” she says.

For a group of people who have dedicated decades to the American chestnut’s rescue, the last few months have been an emotional tumult. “It’s heartbreaking that we’re not further along,” Pitt says. “This wasn’t the silver bullet, but we thought it was a big step.”